AUDIO SUMMARY

ABSTRACT

Employee wellbeing is big business. In 2024, organizations poured nearly €65.25 billion into programs promising happier, healthier, and more engaged workers. From mindfulness workshops to workplace counselling, these initiatives promise a better, more productive workforce. Yet, despite these unprecedentedly well-intentioned investments, workplaces are still in crisis. Burnout has reached epidemic levels, and job dissatisfaction is soaring in all sectors. Further, a growing body of research reveals that these initiatives rarely improve mental health, fail to impact ‘hard’ performance metrics, and almost never delivers meaningful returns on investment. Why are so many wellbeing interventions failing to deliver? And why do organizations keep investing in them?

In this provocative keynote, we’ll explore three critical questions at the heart of this paradox:

- Why do wellbeing interventions fail? There is a myriad of micro, meso and macro causes ranging from prioritising top-down, one-size-fits-all models of wellbeing, through to prioritising quick fixes for symptoms, rather than addressing the systemic causes embedded in their culture and operations. But what else are we missing?

- What causes ineffective interventions to keep living on in organisations? A well-oiled ecosystem of vendors/consultants that sells hope packaged within unproven programs. But it’s not just about clever marketing. Institutional inertia, fear of admitting mistakes, and even unethical practice research practices by academics play surprising roles in keeping ineffective practices alive. Could these forces be blocking real progress, and what else might be at play?

- How can we design interventions that work? The solution lies in making systemic changes and adressing the core issues causing distress AND rethinking how we view and approach wellbeing. By moving away from top-down, one-size-fits-all models of wellbeing, to bottom-up, holistic, person-centred approaches that are rooted in cutting-edge research and real-world success stories, organizations can create lasting, meaningful change. What does this shift look like in practice?

This keynote isn’t just about pointing out what’s broken, it’s about uncovering the hidden forces driving these failures and charting a path toward real, sustainable solutions. Join us to rethink wellbeing and tackle one of today’s most pressing workplace challenges.

INTRODUCTION

“It’s not working.”

That was the thought that sat quietly in my chest as I sat in front of my therapist. This thought haunted me for months before I was ready to say it out loud. Not working like a broken printer or a frozen Zoom call. Not working like something that needs a tweak. I mean these interventions she suggested: is fundamentally not working.

I was a professor of positive psychology at the time. I had published over a hundred papers on wellbeing. I lectured on flourishing, designed interventions to build resilience, helped many organizations build thriving cultures. And yet, there I was… utterly depleted. Not just tired. Not just exhausted. But hollowed out…. Entirely burned out.

I would wake every day at 3 a.m., not because I was energized and ready to take on the day but because I couldn’t sleep. My body was in revolt, my mind was racing, my focus gone; my memory, patchy; my emotional range, flatlined. Later, I would nearly die from a flesh-eating bacteria. But in many ways, I was already rotting away, long before the infection took effect.

You know, the irony wasn’t lost on me. Here I was, someone who taught others how to prevent burnout, and now I was the one crawling through its dark depths. And the wellbeing tools I used… the tools I designed and prescribed… the tools I’d once trusted? They felt like nothing more than sandbags in a flood of despair.

And it wasn’t that I didn’t try them. Man, I did everything. I meditated. I journaled. I practiced gratitude, scheduled self-care, took walks (which I hated), and used every strengths-based hack in the book. But the harder I worked at trying to fix myself, the more it felt like I was being gaslit by my own profession.

If the interventions weren’t working for me… someone trained to understand them, someone who developed them… someone who wanted them to work…. what hope did they have for the average employee in a broken system?

And that’s when it hit me. We weren’t just designing weak interventions.

We were solving the wrong problem.

WHY INTERVENTIONS DON’T WORK

So, I started pulling at threads.

At first, it was just curiosity. Why didn’t any of the things I taught for years helped me when I needed them most? But the deeper I looked, the more the ground beneath me started to shift. Because the evidence was there…. hiding in plain sight.

Take Fleming’s (2024) study on the effectiveness of wellbeing interventions: 46,000 employees across 233 companies. A researcher’s dream. The result? No significant difference in wellbeing between those who used individual mental health interventions and those who didn’t. And in some cases, the interventions actually resulted in worse outcomes. Worse!

Another large-scale trial from the University of Chicago, one of the most rigorous we’ve seen, showed that even after 18 months, wellness programs didn’t move the needle on any important clinical health metrics, absenteeism, or job performance (Song & Baicker, 2019). Their conclusion? We’re spending billions of euros on programs that might make us feel good in the short term… but aren’t actually changing anything that matters.

And there are many more examples showing how in effective interventions are in practice (c.f. Galante et al., 2021 on Mindfulness, Ivandic et al., 2017 on brief interventions in organizations, Renshaw & Steevens, 2016 on Gratitude in Schools, Tomczyk & Ewert, 2024 on ecological momentary positive interventions etc).

I felt angry. Betrayed. And also… Implicated.

Because I was part of this. We all were. The researchers, the consultants, the vendors, the HR departments, the self-help books. All of us. We’d built an industry… no…. a whole ideology around the idea that you could breathe your way out of burnout. That resilience was the solution to toxic work environments or structural disfunction. That wellbeing was just a matter of grit, mindset, and mood tracking.

But then I started listening. Really listening. To practitioners. To employees. To those also suffering from burnout… And over and over I heard the same quiet confession: “We tried it as well… but nothing really changed.” But Why?

Because most of these interventions weren’t designed to work. Not really. They targeted or treated symptoms. Not root causes. A mindfulness app won’t fix an overloaded team or an unmanageable workload. A resilience webinar won’t make a toxic boss less toxic. A gratitude journal doesn’t rewrite structural inequity. We were handing people yoga mats in burning buildings. And worse… we were subtly blaming people for not feeling better.

You’re burned out? Try this breathing exercise. You’re disengaged? Have you tried this new Strengths App? We turned systemic dysfunction into individual pathology. And in doing so, we kept the real problem safely out of frame.

So I wanted to understand this, understand why things didn’t work. So, the more meta-analyses, longitudinal trials, and critical reviews I read, the more I was confronted with a painful truth: the reason these interventions weren’t working wasn’t because they were poorly delivered and it wasn’t because the intentions were bad. It’s because they were never designed to fix the actual sources of our suffering.

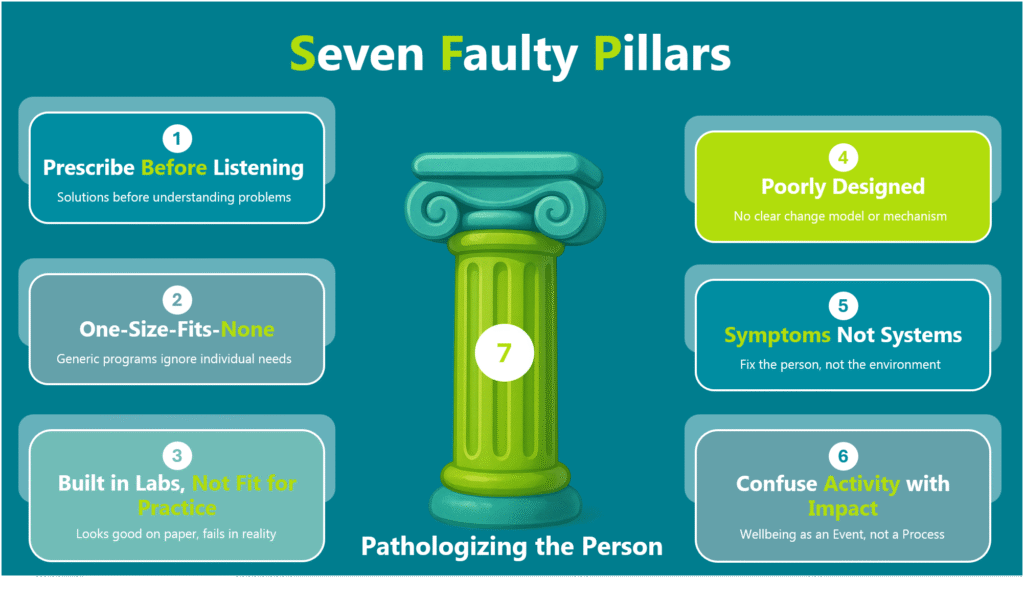

The literature showed me that most wellbeing programs are built on seven faulty foundational pillars:

- They Prescribe Before They Listen

Most interventions start with a solution before understanding the problem. They come pre-packaged, top-down, and theory-driven and are often designed by people that are very far removed from the lived experiences of the individuals they’re meant to improve. The result? A model imposed on people, not shaped with them (Van Zyl & Rothmann, 2019; 2020). - They’re Built for the Average, Not for the Individual

These programs are one-size-fits-all. Handed out like perfume samples at the mall. They are generic, impersonal, and blind to context. They ignore culture, job roles, power dynamics, trauma histories. No tailoring. No nuance. Just a universal prescription for a deeply personal experience (Van Zyl & Rothmann, 2019; 2020). - They’re Theoretically Slick, but Practically Fragile

Many interventions look good on paper. They are “grounded” in behavioural science or backed by shiny citations, but they fall apart when we let them lose in the wild. There’s often no clear logic of change, no meaningful implementation support, and no follow-through. It’s the wellness equivalent of planting seeds in concrete and wondering why nothing grows (Van Zyl & Rothmann, 2019; 2020). - They’re Poorly Designed

Many interventions (both in science and practice) aren’t even built on a solid foundation. In most cases interventions aren’t built on clear empirical models nor was there evidence of any behavioural change model being in place. In other words, there was no logic for how or why interventions was supposed to work. No “needs” analysis. No theory of change. No mechanism. Just a string of “activities” hoping to trigger impact. And almost none of them considered person–intervention fit…. the simple but vital idea that what works for one person might do nothing for another. A journaling app for someone with high cognitive load? A team gratitude exercise for a culture where emotional expression is taboo? No adaptation. No sensitivity. No behavioural scaffolding. Just tools chasing outcomes they were never designed to deliver. It’s theatre, not design (Van Zyl, Effendic et al., 2019). - They Focus on Symptoms, Not Systems

Stress, burnout, and disengagement… these are symptoms of a deeper problem. But instead of addressing the root causes (like workload, toxic management, or role conflict), interventions try to fix the individual. Gratitude journals instead of fair feedback. Breathing exercises instead of boundaries. We pathologize the person, while leaving the system untouched (Van Zyl & Rothmann, 2020). - They Confuse Activity with Impact

Most programs are treated as events, not processes. A webinar on flourishing here. A resilience campaign there. But without continuity, reinforcement, or accountability, the rest of the noise within the organization. Worse, we measure success by participation rates or feedback scores … not by whether anything actually changed (Flemming, 2024). - They Blame the Person

Perhaps the most insidious part of all these interventions are how they quietly shift the responsibility for suffering onto away from the system onto the individual. If you’re burned out, it must be because you’re not resilient enough. If you’re overwhelmed, maybe you just need better time management. We hand people stress balls and mindfulness apps and ask them to “regulate their nervous systems” but we refuse to address the workload, power dynamics, and structural inequities that caused the distress in the first place (Van Zyl et al., 2024; Van Zyl & Dik, 2025).

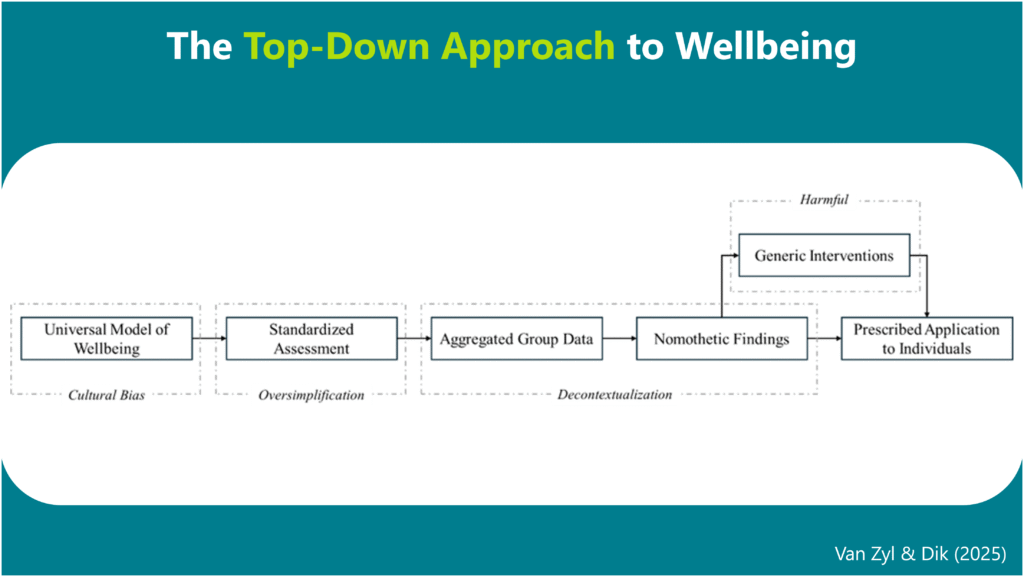

But beneath all that, the most painful realization of them all? Even the most evidence-based intervention won’t work if it’s solving the wrong problem (Van Zyl & Dik, 2025). And that’s what we’ve been doing all along. We’ve assumed that wellbeing is a static, measurable state like blood pressure. That it fluctuates but it’s the same for everyone. That it’s universal. That it can be neatly captured in a survey. That if someone scores low on happiness or high on burnout, that we know exactly what to fix.

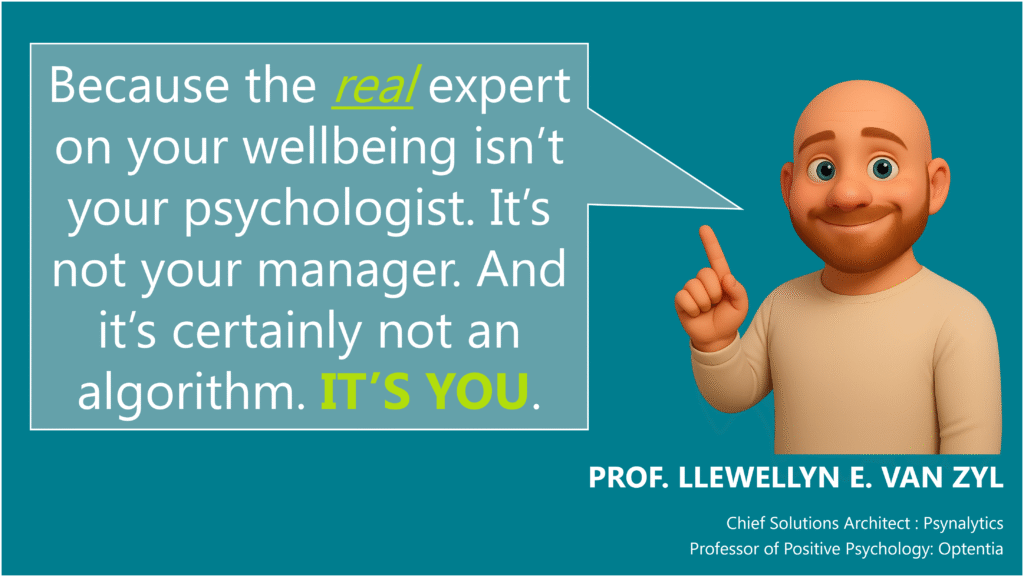

But my dear friends, that assumption is fundamentally wrong. Wellbeing isn’t a number. It’s not a checklist. It’s not a universal recipe. Wellbeing is a deeply personal experience.

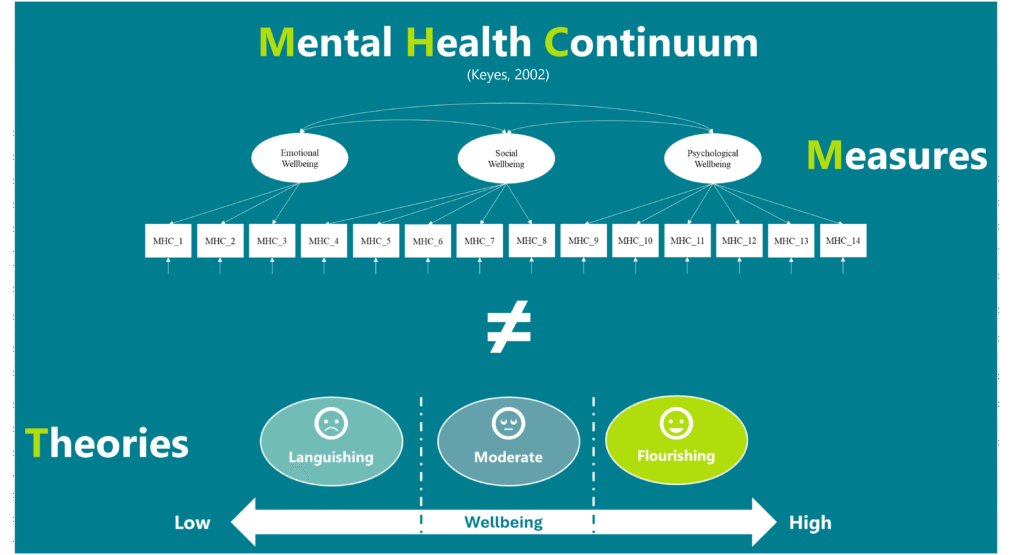

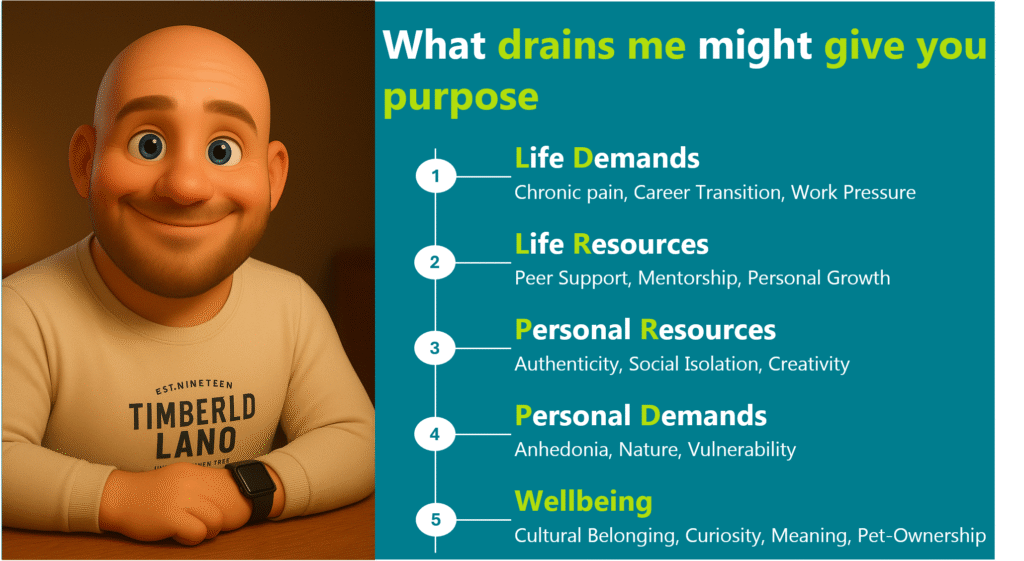

Wellbeing is shaped by culture, identity, values, trauma, relationships, context, history…. What sustains me might mean nothing to you. What drains me might give you purpose. And even the routes we take to wellbeing are different between me and you. Yet we keep building interventions on top of these top-down prescriptive models of wellbeing like PERMA or the MHC that dictate to us what wellbeing is (Van Zyl & Dik, 2025).

And our theories aren’t even aligned to our measures (Van Zyl et al., 2024). Like Keyes (2002) indicates that Mental Health is a function of a dynamic interaction between Emotional, psychological and social wellbeing and that mental health is on a continuum. Yet its measured as CFA factors and the continuum modelled as three categories (languishing, moderate mental health and flourishing: c.f. Figure 2) (Van Zyl & Ten Klooster, 2022). That’s insane! We then use these generic surveys to measure and benchmark people as if flourishing looks the same for a nurse in Lagos and a coder in Rome. As if a one-dimensional scale can tell someone what their “wellbeing level” is. No wonder the interventions don’t work. We’re trying to force individuals into a model and forgot about the person (Van Zyl & Dik, 2025).

So if we’re serious about making change… And I mean real, sustained, human change… we have to stop designing interventions from prescriptive theories with excellent marketing and start designing from individuals lived experiences (Van Zyl & Dik, 2025). In other words, not from what a professor says wellbeing should be. But from what the person living it says it is.

Until then, no amount of coaching, meditation, or psychological tinkering will work. Because the intervention might be precise. But the target? Entirely wrong. And once you realise that… you can’t unsee it.

WHY DO WE KEEP USING INTERVENTIONS THAT DON’T WORK?

So if we know the interventions don’t work, then the natural question becomes… why the hell are we still using them? Why do we keep selling them? Why do organizations still invest in yoga matts and wellness apps while their employees quietly drown?

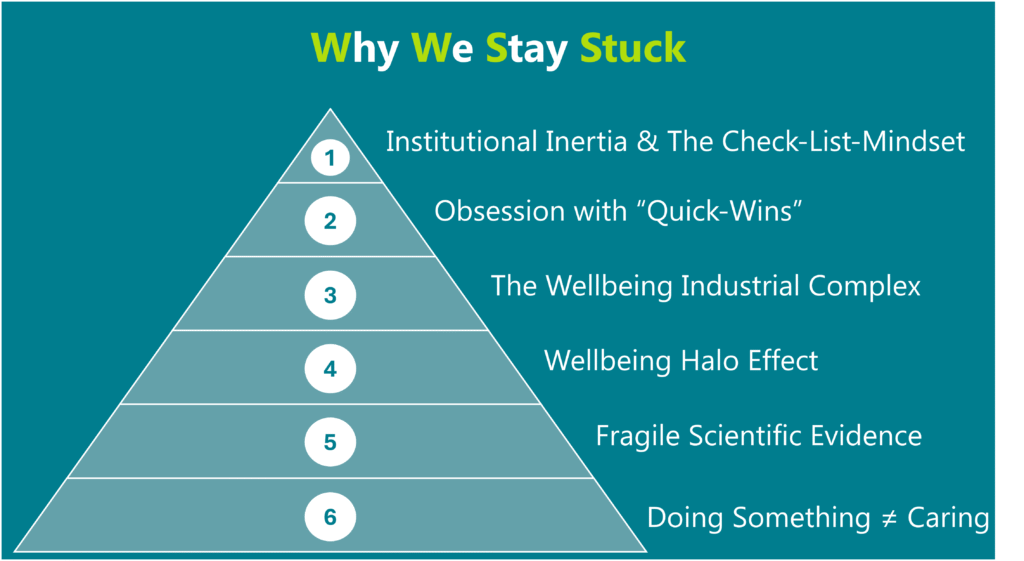

I’ve asked myself this question more times than I can count. And the answer is… (dramatic pause) …. not simple. It’s not stupidity. It’s not laziness. It’s not malicious intent. It’s a whole ecosystem of pressures, biases, and beliefs that’s all working together to sustain a cycle that no one really wants to be in, but few are willing to break. A self-reinforcing loop of incentives, blind spots, and inertia that keeps us trapped in this cycle of shiny-but-shallow solutions. So why do we keep using interventions that don’t work?

Well, there’s six reasons

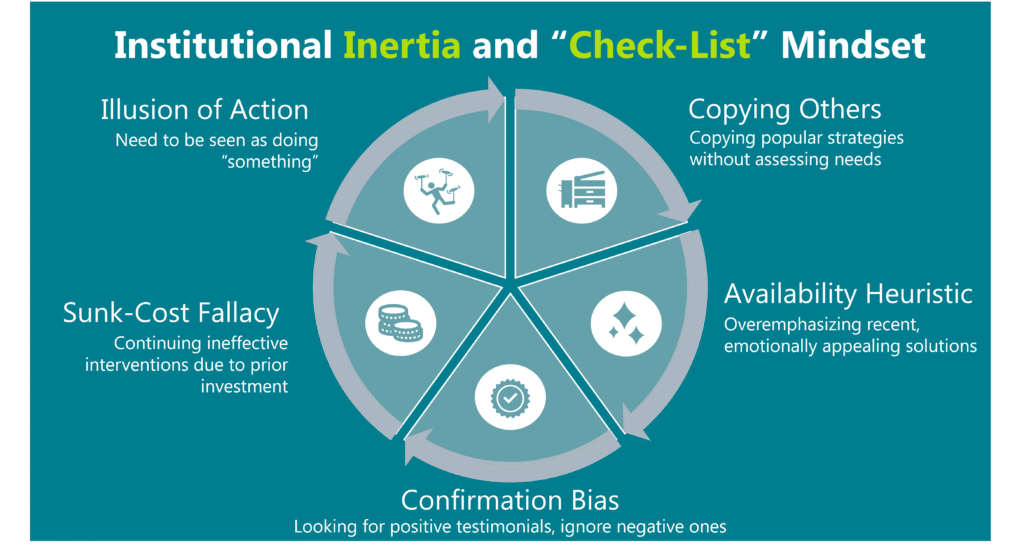

The Illusion of Action: Institutional Inertia and “Check-the-Box” Mentality

Let’s start with the obvious: we’re afraid to admit failure. Once a company sunk money, time and reputation into a wellbeing strategy, going back to the board and admitting that “this didn’t work” feels risky. No, it’s dangerous. It’s easier to double down, tweak the language, roll out a new version than to go back to the board and say, “We’ve been measuring the wrong thing. Solving the wrong problem. We need to start again… and um… can we have more money?”

But underneath that fear is something deeper, something more human, something I’ve felt myself…

It’s the need to be seen as doing something. Especially if you’re in leadership. Especially if you’re in HR. When burnout spikes or engagement tanks, you can’t just say “we’re working on it.” You need to show action. A campaign. A platform. A dashboard. A vendor. A line on the budget that says: we care.

And that’s how interventions become theatre. They became the visible proof of care. Even if they don’t work. But the system doesn’t just reward appearances. It’s also wired to keep us stuck in these practices we know don’t work

Like, we fall victim to the sunk cost fallacy. We’ve already paid for the platform, its already been socialised internally, so let’s just keep renewing it, even when no one actually uses it anymore.

We latch onto confirmation bias, where we look for that one glowing testimonial about the mindfulness challenge that supports our idea that mindfulness work. We frame it nicely in a slide deck, while quietly ignoring the 200 other people who quietly disengaged after week two.

Then there’s the availability heuristic where our brains give more weight to what’s shiny, new/recent, and taps our emotions. Like that slick new wellbeing vendor, we saw at a conference with that “AI-Driven Gamified Wellbeing Experience”. It felt cutting edge. It had a dashboard. A UX like Netflix. We remember that. Not the meta-analysis with 18,000 participants buried in a journal we never finished reading.

And finally, there’s this need to mimic others. The quiet pressure to copy what the big players are doing. If Google has a resilience program, we should too. Not because there is a need. Not because it fits our culture. But because it’s safer to follow the herd than to do something original that might not work. Obsession with Quick Wins

We also have this inherent obsession with quick wins and ‘low hanging fruit’… Things we can use to prove ROI before the quarter ends. Leaders want pretty numbers they can present: “500 employees participated,” “stress dropped by 12%.” It sounds impressive. But what we rarely ask is: Did anything actually change? Were people still burnt out six weeks later? Did anyone feel safer, more seen, more human? Structural change takes time. Cultures don’t change on a neatly defined campaign timeline. But that kind of long-haul care doesn’t look good in a slide deck because it requires work and is expensive. So it’s easier to reach for wellness challenges instead of redesigning our work systems. We prioritise what’s fast over what’s real. And then we wonder why nothing works

Hope for Sale: The Wellbeing Industrial Complex

And then, of course, there’s the wellbeing industrial complex. The corporate wellness industry is now worth over $90 billion. And like any industry, it’s built to sell. It’s therefore not surprising that we have an entire market of vendors, platforms, consultants, and certification schemes trying to sell us hope in a neatly packaged corporate jacket. Most of them dressed in the language of science, but rarely backed by rigorous, transparent evidence. Some of them mean well. Some of them are snake oil. But all of them are selling to a system that wants quick and dirty solutions. Preferably digital. Definitely Scalable. Easy to pilot. Easy to measure. This is what I call the techno-solutionist fantasy… that we can solve human suffering with a UX update.

But these solutions don’t really offer change. What they really sell is control. They allow organizations to act on wellbeing without actually relinquishing any power or making any changes to the actual system. You don’t have to change your managers. Or rethink your values. Or share decision-making with the people doing the actual work. No, you just give them a tool. And then you say, “We did our part.”

Looking Like We Care: The Wellbeing Halo Effect

The truth is that wellbeing sells. It’s good PR. It makes companies look progressive, ethical and human. And because “wellbeing” is such a positive, wholesome word, it tends to escape the scrutiny which other organizational initiatives (like restructuring) is subjected to. It creates a type of halo effect where the mere appearance of caring is mistaken for care itself.

This is where “carewashing” creeps in.

You can launch a digital wellbeing portal while still incentivizing unpaid overtime. You can post Mental Health Awareness Month quotes on LinkedIn, while you are still ignoring how your CTO is bullying his team. You can run a resilience campaign while your employees are too scared to take a lunch break.

But I don’t think its always malicious. Often, it’s just unconscious. But it’s still dangerous because when the rhetoric of care doesn’t match the reality of work your people wont feel supported. They feel betrayed. And when betrayal happens enough times, cynicism sets in. Trust erodes. And the next time someone tries to introduce a real, meaningful intervention? No one shows up.

Counting What’s Easy, Ignoring What Matters: Measures that Don’t Matter

The next problem is that we are measuring the wrong things. We count sign-ups. Participation rates. Smiley-face feedback surveys. We use top-down organizational diagnostic models dictating what the demands, resources and stress/motivational factors are that your organization faces. But we rarely track and ask whats really going on for each individual employee or whether people feel more human at work. Our metrics are shallow because the system rewards short-term optics over long-term change.

Fragile Truths and Friendly Lies: The Role of Academia

And let’s not ignore academia’s role here either. There’s a knowledge-practice gap the size of a canyon. We publish studies with promising results in tightly controlled conditions, and they get lost in translation when scaled into messy, complex workplaces. And let’s be honest.. we almost always overhype our own findings. We present small effect sizes like they’re silver bullets. Because nuance doesn’t sell.

And here’s the part academics don’t want you to know: when the data doesn’t cooperate, we like to shift the story we tell. We try to rationalize. We try to reframe. We try to blame the context. And we publish the stuff anyway. Because no one wants to write, or read, “We tried to improve wellbeing and nothing happened.” So instead, we find some statistically significant breadcrumb… a p-value in a corner of the data… and we start spinning. Or worse: we wrap the non-significant effect up in a fancy jacket with pristine language, dressed up with theoretical justifications, and send it off to peer review… Selling the idea that our interventions worked… when in fact… they didn’t.

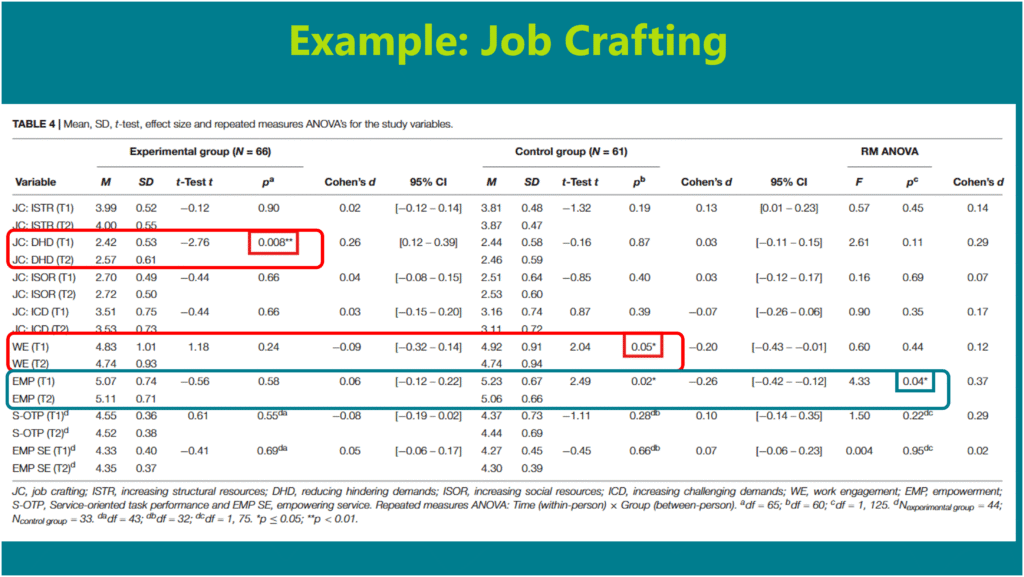

For example, there was a job crafting intervention study at an unemployment insurance agency a few years ago (Hulshof, Demerouti, & Le Blanc, 2020). According to the statistics in the paper (see figure below), there was no difference between the intervention group and the control group. None

Looking at the within-group results, there were slight and anecdotal changes in “Reducing hindering demands” and within the control group there was a small decrease in “Work Engagement” (c.f. Table 4 in the paper). But instead of concluding that the intervention didn’t work, they whole heartedly shouted off the proverbial roof tops that their intervention was a resounding success. Why? Because the company had announced an upcoming restructure and restructures, as we know, brings about a lot of anxiety, job insecurity, and stress. The logic was pretty clear: if wellbeing didn’t drop, it meant the intervention buffered people from the stress and anxiety that usually comes along with an organizational restructure. But here’s the problem: the restructuring was only announced a few weeks before the final measurement was taken. The intervention didn’t buffer anything. Nothing changed because nothing worked. But the paper framed it as a triumph of psychological protection.

My dear colleagues, that’s not just being an academic spin doctor. That’s misleading you with a friendly face.

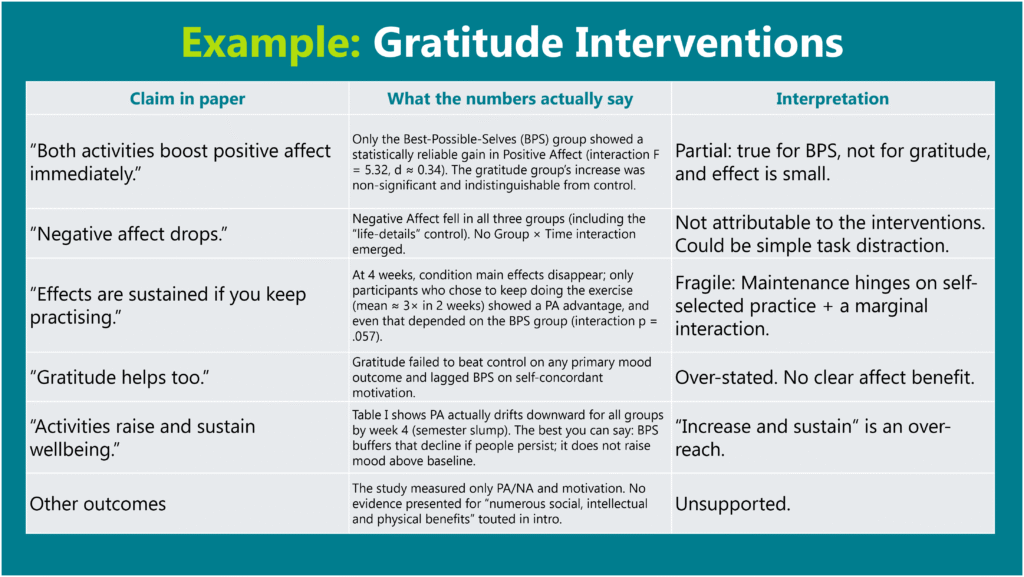

Another example comes from one of the field’s most cited gratitude studies (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006) who used just 67 psychology students to test the effectiveness of the “Best possible selves” exercise and gratitude on reducing negative affect and improving positive affect (See summary in figure below).

Over four weeks they either listed things they were grateful for, imagined their best possible selves, or simply wrote daily details. Gratitude failed to raise positive mood above the control task, and its “near-significant” p = 0.11 fizzled by week four unless students kept journaling, which most did not. Only the best-possible-selves exercise produced a small, short-lived increase in mood that was not sustained (d ≈ 0.3). Yet the paper is still cited hundreds of times as proof that gratitude interventions work…. an example of how tiny, fragile effects become oversized claims in our literature.

A recent meta-analysis by White et al. (2019) looked at the effectiveness of positive psychological interventions and found that (a) the majority used small samples (with student groups!), (b) small sample bias was present in almost all the analysis in these studies, (c) that these interventions’ effects on wellbeing was small (r = 0.10 – almost anecdotal), and most importantly (d) that their effect on depression was just dependent on outliers and generally not statistically significant.

And this isn’t just about these study. It’s a mirror for how our entire field works. We take short-term, small-sample, barely-there effects… and we spin them into evidence-based programs. We sell interventions that “increase wellbeing,” when the truth is, they made a handful of undergrads feel a little better for about a day.”

And we’re all guilty of it. We overstate effects. We claim “potential” based on marginal p-values. We cherry-pick context to make the story fit. Why? Because nuance doesn’t get cited. Honest failure doesn’t get funded. Reviewers want impact. Journals want novelty. Institutions want headlines. So, we keep the machine going… paper after paper, intervention after intervention… even when, deep down, we know the field is saturated with inflated claims and fragile truths. We say we care about wellbeing, but sometimes I wonder if we care more about being right. And in doing so, we don’t just undermine the very credibility we need to create workplaces that actually support people, but we are harming them in the process by presenting false claims of effectiveness.

When Doing Something Isn’t the Same as Caring: The Numbness of Good Intentions

But perhaps the most insidious reason we stay stuck? These interventions let us feel like we care… without having to act like we care. They help us avoid having hard conversations. The real work. The hard work. The vulnerable work. Because it’s so much easier to offer employees a meditation room than to ask them what part of their job is slowly breaking them. It’s easier to roll out a resilience training programme than it is to confront a high-performing toxic manager who leaves psychological wreckage where ever they go. It’s easier to send out a pulse survey than to actually ask what would actually make people’s lives more liveable and then act on it.

We say we want to support our people. But when that support would require changing the way we lead, staff, budget, or manage? Suddenly, that old playbook starts looking very attractive again. Why?

Because it creates the illusion of compassion while we can keep protecting the status quo.

Because it’s safer.

Because it’s known.

Because it’s… “better than nothing.”

But what if “better than nothing” is actually worse than nothing?

Because it breeds cynicism and discontent. It creates a kind of emotional bait-and-switch where people are told, “We care about your wellbeing,” while still being micromanaged, overworked, and under-supported. And when people start to see that gap between what we say and our lived reality? They don’t just disengage… they stop believing. They stop trusting. They stop caring.

So, we end up with programs that soothe the guilt of leadership more than they reduce the suffering of their staff. Programs that create noise instead of change. Comfort instead of care.

And maybe that’s the most dangerous thing of all is that all our good intentions have become a type of numbing agent. A way for us to avoid the harder, more uncomfortable questions.

What if these well-meaning, well-funded, well-branded programs are just numbing the pain… distracting us from the systemic roots of suffering? What if our loyalty to what feels comfortable is the very thing holding us back from what actually works?

Taken together, these factors aren’t just bad habits. They’re built into the nervous systems of our modern organizations. And unless we name them, they’ll keep steering us back to the same polished but ineffective playbook…. no matter how loudly the data protests.

FROM PATCHWORK TO PROCESS: WHAT ACTUALLY HELPS PEOPLE THRIVE

I’ve stopped asking, “What’s the next big wellbeing trend?” Instead, I’ve started asking, “What would a system look like that didn’t make people sick in the first place?”

Because here’s what I’ve come to believe: the future of wellbeing isn’t a tool. It’s a transformation.

It starts with a simple but radical shift in our thinking and our approach. We should stop trying to fix individuals, and start fixing the environments they’re in. We stop treating burnout like a personal failure and start seeing it as a signal… no, a symptom of broken work design, of chronic overload, of a system that rewards output at the expense of oxygen. And the evidence backs this up.

Structural Changes and Interventions

The WHO’s 2022 guidelines on mental health at work didn’t recommend mindfulness or resilience as frontline strategies. They told us to focus on workload, managerial behaviours, job design and addressing structural and systemic issues. Not adopting more apps.

And what about William Fleming’s study? The only types of interventions that consistently improved wellbeing? Organizational Level Interventions. The interventions refer to structural shifts that addressed the actual friction points inside the work itself which range from participatory job redesign to improved leadership feedback loops to changing work-time arrangements that gave people more autonomy and control. These weren’t perks. They were process shifts. They altered the system.

So what does this mean for us… as psychologists, consultants, leaders?

It means we stop outsourcing care to tools and start building cultures where care is structural. It means we ask harder questions. Like: What’s draining people? Where’s the friction? Who’s being excluded?

It means have to start swimming upstream. We stop hunting for magic bullets and start engaging in deep organizational diagnosis. Not a five-minute pulse survey but by using real data. Mixed methods. Psychosocial risk assessments. Managerial behaviour audits. Listening circles that go beyond the sanitized dashboards.

We start redesigning work so that rest isn’t something you have to earn bur rather it’s something that’s structurally embedded and protected. We reduce meeting overload. We remove unnecessary complexity. We fix the bottlenecks. We change workflows to allow deep work. We rethink how we evaluate performance, so that productivity doesn’t become a proxy for self-worth. We normalize “off” as much as we celebrate “on.” And we get more honest in how we evaluate our efforts. Not just, “Did people like it?” but, “Did anything actually change?”

We train managers, not just in compliance or OKRs, but in the skills that will actually help them build the wellbeing of their teams: relational intelligence, appreciative feedback, fairness, support… These are not soft skills, they are the infrastructure on which a healthy system is built.

We also stop looking for scalable plug-and-play programs and start investing in co-designed, context-specific interventions that are built with and not not just for employees. This means engaging teams in the very design of the interventions they’ll experience. Not a vendor’s idea of care, but the team’s own articulation of what’s needed, what would help, what care feels like to them.

And then we measure not just “Did people like it?” but “Did anything actually change?” Did stress decrease? Did autonomy increase? Did psychological safety shift? Are people more likely to stay, more willing to speak, more able to breathe?

But this doesn’t mean we have to throw away individual level interventions. They still matter. But only when they’re personalized, voluntary, and offered in a context that supports real healing. But they should be the side dish, not the main course. The main course is equity and structural changes. Real wellbeing isn’t a perk. It’s a design outcome. And the more we understand that the more powerful our work becomes.

Call for Person-Centered, Idiographic Models of Wellbeing

But even the best structural changes that employs the most effective organizational redesign processes, people centred policies, and effective leadership development processes will only take us so far if they’re still built on the wrong map.

And that’s the deeper shift I didn’t really see at first. Maybe because I was too embedded in the system, too fluent in the frameworks and language of PERMA and the Mental Health Continuum and perhaps to passionate about the potential of my discipline. I was too focused in trying to understand why these interventions didn’t work for me, and didn’t see that the problem might be the exact building blocks on which they were supposedly built.

So after about a year, I realised it’s not just the interventions that are wrong. It’s the entire way we define wellbeing.

We’ve spent decades building top-down models and elegant frameworks like PERMA or the Mental Health Continuum which were designed to measure what we’ve decided “good” looks like. And don’t get me wrong: they’ve done important work. They’ve given us language. They’ve given us structure. But they’ve also done something more subtle… and more dangerous.

These top-down models of wellbeing started to tell people what their wellbeing should look like. As if flourishing were a checklist. As if we could universalize something that is, at its core, deeply personal, contextual, and dynamic.

What we’ve overlooked … and what I now believe is the missing piece… is that wellbeing isn’t a fixed set of outcomes to be achieved. It’s a lived, evolving and deeply personal experience. It’s how you define what matters to you, in your life, in your language, on your terms. It’s not just about how you feel, it’s about what you value, what you’re moving toward, and what feels like “enough.”

The problem with our current models is that they treat wellbeing like a standard product, not a personal process. We build interventions to “increase happiness” or “boost engagement” as if those mean the same thing for everyone. We apply instruments that don’t translate across cultures, jobs, life stages… let alone across individuals.

But what if the problem isn’t that our tools are too weak, but that they’re too generic?

What if the real shift isn’t just designing better interventions, but designing better ways of understanding?

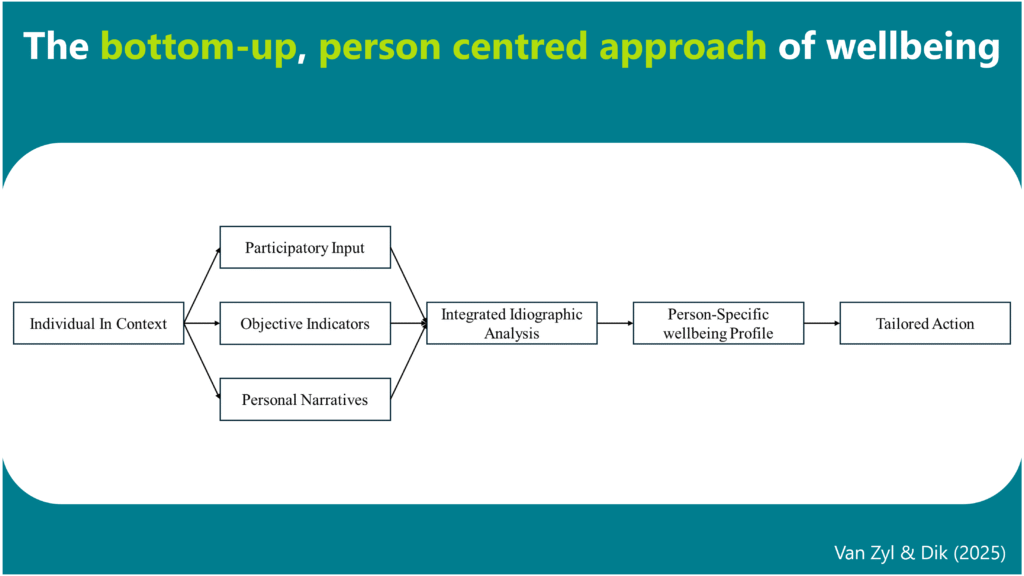

This is where bottom-up, person-centred, idiographic models of wellbeing come in. These approaches are designed from the bottom-up and starts with the person, not with a theory. Where the first question isn’t “How do you score on PERMA?” but rather “What does wellbeing mean to you?” Where measurement adapts to the individual’s context, rather than the individual being crammed into a model that wasn’t made for them.

Elements of a Bottom-Up, Idiographic Person-centred Approach

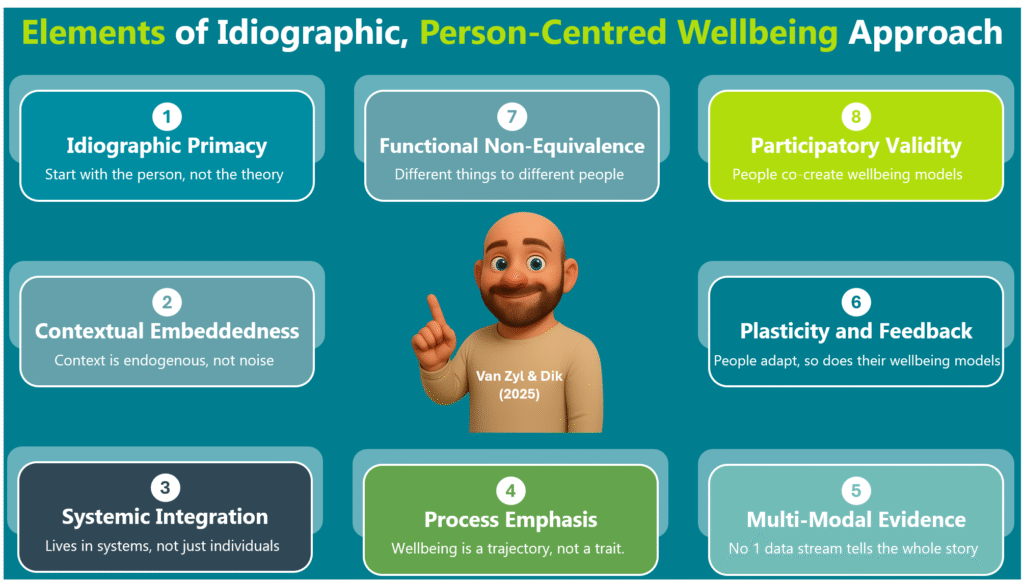

To lay the foundation of this bottom-up, idiographic person-centered approach of wellbeing, we have to clarify the principles on which its built. These design principles provide the philosophical and procedural scaffolding for an idiographic science of wellbeing. Below is a summary of the 9 elements building out this approach:

It starts with a commitment to idiographic primacy. Here we see each person as a unique system, a case study unto themselves. We don’t average people into categories. We don’t jam them into models. We build a wellbeing model from their understanding and lived experience… using their data, their language, their definition and their life as the unit of analysis.

Second, it means we need to realise that wellbeing is contextually embedded. Its not something that floats above or within a person but rather it something that lives within their environments. Neighbourhood safety, cultural obligations, climate stress, income instability etc… These aren’t background variables we need to control for. They’re causal forces that live within each person’s wellbeing network. When we stop treating context as noise and start seeing it as signals, we can truly understand what wellbeing is for a person.

Third, the individual is embedded within a series of integrated and inter-related systems. It took me a while to see it, but wellbeing doesn’t live in the individual, it lives in the systems around them. We can’t separate someone’s stress from their childcare access, or their anxiety from the housing crisis they’re quietly navigating. Wellbeing is shaped by policies, histories, neighbourhoods, and power structures. So when we build models that ignore those layers, we’re not simplifying… we’re ignoring the importance of how systems interact and affect one another.

Fourth, we shift our focus from taking snapshots of wellbeing to seeing it as a deeply personal process. In other words, wellbeing isn’t a trait…. it’s a trajectory. So, we track how a person feels, thinks, copes, and connects across time. Through daily check-ins. Narrative prompts. Momentary assessments. We start to see how people change, when, and why. That’s where real insights live.

Fifth, we start gathering multi-modal evidence to understand wellbeing of the individual from different perspectives. Because no single source of data can capture a person’s full reality. So, we need to combine their personal stories with psychometrics and objective indicators. Diaries with wearables. Mood with environmental sensors. Personal narratives with community-level data. Self-reports with macro level factors (e.g. GDP, Inflation etc). Yes, it’s a lot messier but it’s more honest. More complete. More person-centered.

Sixth, wellbeing systems aren’t static, they are built for plasticity. People aren’t static, and neither is their suffering. We adjust. We reframe. We learn. We change. Sometimes it’s a promotion, a conversation, or just a moment of quiet clarity and suddenly the same stressors that felt overwhelming feels totally different. That’s what plasticity is. The system learns, and if we’re paying attention, we can see that change happening in real time.

Seventh, the same condition can promote or impair wellbeing for different people (i.e. functional non-equivalence). The same condition doesn’t mean the same thing to everyone. Loneliness might break one person’s heart and give another the space to heal. Stress can drain you or drive you, but it depends on the person, the meaning they attach to the stressor, and their context. So instead of asking whether something is “good” or “bad,” I’ve learned to ask, “What role does it play…for you?”

Eight, we prioritise co-creation or “participatory validity” when building wellbeing models. This means the participant isn’t just a subject we need to understand but rather they are co-creators. They define and review their own models. They adjust the labels. They question the links. They say: That’s not what I meant. And we listen. Because they’re not data points. They’re experts in their own lives.

And finally, we act or intervene. But only when we know where to act and what to do. We use computational tools and N-of-1 experiments to pinpoint what matters most in that person’s network. Maybe it’s adding a moment of quiet after taking the kids to school. Maybe it’s reducing their social obligations. Maybe it’s changing how they think about conflict at work. And then we test those changes, gently, iteratively and with compassion… until something starts to shift.

Only after all this…. the deep listening, the intense modelling, the genuine feedback, the partnership… do we begin to look for patterns across people. Not by flattening them into averages, but by clustering the complexity. That’s how we build new theories: not by guessing, but by listening. And not by removing differences, but by learning from it.

Once you see wellbeing as something personal, emergent, and co-created… everything changes. You stop designing programs based on averages. You start designing with people, not for them. You stop asking “Does this intervention work?” and start asking, “For whom? Under what conditions? And according to whose definition of better?”

We talk about meeting people where they’re at. But that only works if we actually listen. And here’s the thing: when we do…. when we stop prescribing and start partnering with people we will actually see them respond to our treatments and interventions. They open up. They engage. They trust. They change. Because for the first time, we’re not trying to fix them. We’re finally seeing them.

And that’s what I want the future of wellbeing to look like.

Not just interventions that work. But models that respect complexity and the lived experiences of the individual. Programs that are co-authored and not just attended. Systems that are deeply human before they are efficient.

CONCLUSION: WHAT IF WE JUST LISTENED

So where does this leave us?

For me, it didn’t end with a breakthrough or recovery. It ended with a question. A slower life. A different pace. A bit more silence. A bit more softness. I stopped pretending I could measure my way out of exhaustion. I stopped trying to “fix” myself with the tools that wasn’t designed for me.

I didn’t come here with a new framework to sell you. I didn’t fly to Italy to present you with the next hot model. I came to tell you a story…. one that started with a collapse, moved through disillusionment, and landed in something softer, truer, and maybe more useful.

I’m here because I believe that maybe, just maybe, we can build something better together… not by being certain, but by being honest. Curious. And Human. And that that maybe the most radical move we can make in this field… is to stop pretending we have the answers.

I believe our job is to stay curious. To build systems that are honest. Models that are open. Interventions that ask more than they assume. Maybe that’s the most radical move we can make in this field is to admit that we don’t know. To let go of the blueprints and check-lists. And to begin again… not from theory, but from the person in front of us.

Because wellbeing was never a template. It was never a program. It was never a metric. It’s a question. And we need to start listening.

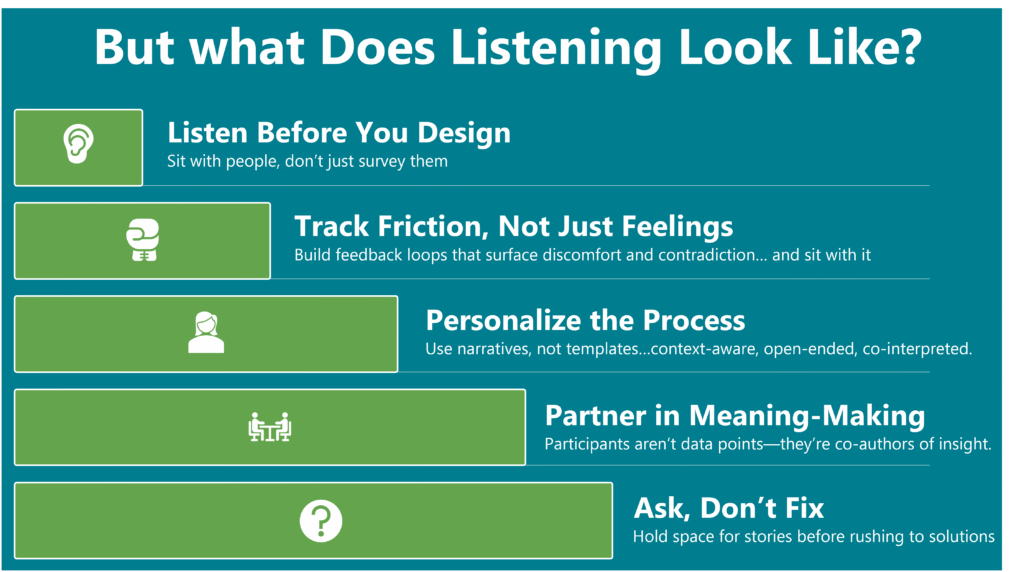

But what does listening look like in research and practice.

- It means that before we design a wellbeing programme, we sit with employees (not just survey them) and ask them to describe, in their own language, what gives their work meaning… and what quietly drains the life out of it.

- It means building heuristic feedback processes that don’t just track happiness or job satisfaction, but rather ones that help us uncover friction, complexity, contradiction … and then staying with that discomfort long enough to understand it.

- It means replacing one-size-fits-all diagnostics with open-ended narrative interviews, daily reflections, context-aware sensing and involving people in the interpretation of their own data.

- In research, it means that the participant shouldn’t be seen as another data point. They’re co-authors of the study. A meaning-maker. A human system of language, values, and memory. And our job is not to make sense OF them but WITH them.

- In practice, it means we resist the urge to fix. We learn how to ask better questions. And we create the conditions for stories to naturally emerge.

But perhaps the most honest thing I can say, after all of this, is that I don’t know what wellbeing looks like… for you. But I want to ask. I want to listen. And I want to know.

Because it’s not working.

But maybe now… we finally know where to begin. By asking the most radical question of all:

What does wellbeing mean… to you?

And then… shut up. And listen.

Grazie.

REFERENCES

- Fleming, W. J. (2024). Employee well‐being outcomes from individual‐level mental health interventions: Cross‐sectional evidence from the United Kingdom. Industrial Relations Journal, 55(2), 162-182.

- Galante, J., Friedrich, C., Dawson, A. F., Modrego-Alarcón, M., Gebbing, P., Delgado-Suárez, I., … & Jones, P. B. (2021). Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS medicine, 18(1), e1003481.

- Hulshof, I. L., Demerouti, E., & Le Blanc, P. M. (2020). Providing services during times of change: can employees maintain their levels of empowerment, work engagement and service quality through a job crafting intervention?. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 87.

- Ivandic, I., Freeman, A., Birner, U., Nowak, D., & Sabariego, C. (2017). A systematic review of brief mental health and well-being interventions in organizational settings. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 99-108.

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of health and social behavior, 207-222

- Renshaw, T. L., & Olinger Steeves, R. M. (2016). What good is gratitude in youth and schools? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of correlates and intervention outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 53(3), 286-305.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The journal of positive psychology, 1(2), 73-82.

- Song, Z., & Baicker, K. (2019). Effect of a workplace wellness program on employee health and economic outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 321(15), 1491-1501.

- Tomczyk, S., & Ewert, C. (2025). Positive changes in daily life? A meta‐analysis of positive psychological ecological momentary interventions. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 17(1), e70006.

- Van Zyl, L. E. (2025). Exploring Potential Solutions to the Criticisms of Positive Psychology: Can the Bold, Idealistic Visions of Positive Psychologists Survive Real-World Scrutiny. Frontiers in Psychology, 15(1511128), 1-32.

- Van Zyl, L. E., & Rothmann, S. (2020). Positive organizational interventions: contemporary theories, approaches and applications. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 607053.

- Van Zyl, L. E., & Rothmann, S. (Eds.). (2019). Positive psychological intervention design and protocols for multi-cultural contexts. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Van Zyl, L. E., & Ten Klooster, P. M. (2022). Exploratory structural equation modeling: Practical guidelines and tutorial with a convenient online tool for Mplus. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 795672.

- Van Zyl, L. E., Efendic, E., Rothmann Sr, S., & Shankland, R. (2019). Best-practice guidelines for positive psychological intervention research design. In Positive psychological intervention design and protocols for multi-cultural contexts (pp. 1-32). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Van Zyl, L. E., Gaffaney, J., van der Vaart, L., Dik, B. J., & Donaldson, S. I. (2024). The critiques and criticisms of positive psychology: A systematic review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 19(2), 206-235.