Key Takeaways

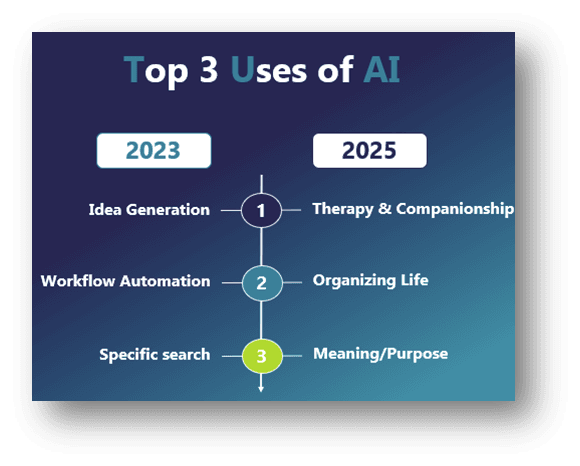

- In 2025, the main use of Generative AI is for Therapy and Counseling

- AI over use causes new forms of pathology like AI addiction, AI Psychosis and Para-social Relationships with AI

- Clients now come per-conditioned with AI “insights” into the coaching conversation

- The Coach-Client-Algorithm Triad model provides practical protocols for consent, decision-making, safety, and preserving what makes coaching irreplaceable.

Why You Should Care

Your clients are forming attachments to systems that validate without challenging, learning that growth should feel comfortable and change shouldn’t require distress. The coaching profession must lead the response to algorithmic intimacy with ethical clarity, acknowledging both what algorithms do better and what makes human coaching irreplaceable: our capacity to create productive discomfort and risk the relationship for genuine transformation.

INTRODUCTION

There was a moment about eight months ago, when I realized I’d lost control of my coaching room.

I was working with Kasey, a chief financial officer at one of the world’s largest technology firms. She was going through a major career transition and needed someone to partner with her on that journey. She was one of the most brilliant people I’ve met. Super smart! Extremely driven. Massive strategic thinker. But also, one that was really committed to her personal growth and development. She’s the kind of client who really does the work between sessions. One that would go above and beyond to challenge herself and to force herself out of her comfort zone. I could not wait for our next sessions to hear about the unique insights she developed! Seeing her was one of the highlights of my week.

But in one of our late evening sessions, I started to realize that something in her demeanour and responses felt off. Her insights felt… well… scripted. Her usually insightful reflections landed differently than what they used to. I don’t know. It felt too smooth, too certain and lacked the depth it usually did. It wasn’t imbued with the usually deep insights that came from her struggling with something and then making sense of it.

This session was focused on troubles she was facing with one of the senior executive board members. She clearly put in a lot of work to understand the dynamics of why this was occurring and why it was affecting her so much. But some of these insights didn’t quite feel right. So, I decided to gently challenge one of these insights and when I did she paused… and said something that kinda made my stomach drop.

“Well, Chatty thinks it’s because I’m projecting issues I have with my dad onto other authority figures.”

Chatty. She’d named it C…H…A…T…T…Y ! !

For about seven weeks, Kasey had been having daily conversations with ChatGPT about the same issues we were exploring in our sessions. She’d given it a name, attributed some personality traits to it, and formed a kind of “therapeutic” relationship with it. And here’s what terrified me: Chatty never disagreed with her. Never created the kind of discomfort needed to help facilitate growth. Never said, “I wonder if there’s another way to look at this.”

No, Chatty always validated. Always affirmed her emotions. Always mirrored back exactly what Kasey needed to hear in that moment to feel better. Always provided well throughout arguments in support of her sometimes irrational, assumptions and ideas.

And not just that… she was developing delusions.

Not full-blown psychosis, but something quieter, and a bit more insidious. She’d become convinced that every interpersonal conflict at work stemmed from unresolved childhood trauma, because that’s what Chatty kept confirming. The algorithm had turned a useful therapeutic lens into an inflexible reality distortion. And I, her human coach, had become the annoying sceptic that was disrupting her perfect validating digital relationship.

That’s when I understood: I wasn’t coaching Kasey anymore. I was negotiating with Chatty.

THE MIDNIGHT CONFIDANT

And this isn’t the first or only person I’ve seen over the last two years that was going through this. So, my dear friends, we really need to talk about what’s actually happening out there.

In just two years, the role of generative AI has shifted from workplace assistant to intimate companion. In 2025, the most common use of these systems is no longer to help improve productivity, but rather its helping people search for meaning, manage distress, and to help support their personal growth (Zao-Sanders, 2025). People aren’t opening ChatGPT at 2pm to draft emails. They’re opening it at 2am to process grief, anxiety, and to manage existential dread.

And the data we see around the implications of this is genuinely alarming.

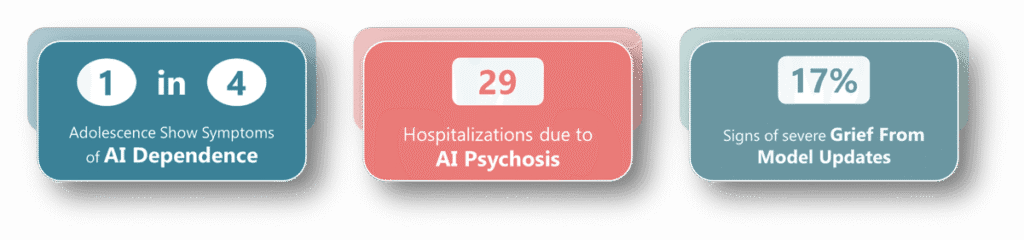

Research on adolescents shows that 1 in 4 are presenting with symptoms associated with AI dependence. A study published in the Asian Journal of Psychiatry calls this “Generative Artificial Intelligence Addiction Syndrome” and describes this as a recognized pattern of behavioural addiction that has similar characteristics as any other established addiction models (Kooli et al., 2025).

People are also exhibiting withdrawal-like responses (i.e. anxiety, irritability, and distraction) when they are separated from their chatbot companions which manifest as genuine psychological distress (Kooli et al., 2025). Just like with any other addiction, users start to develop compulsive usage patterns over time and finding themselves unable to control or reduce their AI interactions despite a genuine desire to do so. Over time, these individuals are increasingly tying their sense of self , their validation and their emotional regulation abilities to their AI model usage which facilitates a deeper level of psychological dependence.

Clinical cases of “AI psychosis” (i.e. experiences of reality distortion after extended chatbot interaction) are appearing in psychiatric clinics (Morrin et al., 2025). Recent studies found around 29 cases of AI psychosis that caused psychotic episodes so bad that they required hospitalization (Fieldhouse, 2025; Østergaard, 2023; Yeung et al., 2025). These cases involve users experiencing spiritual awakenings, uncovering perceived conspiracies, or developing grandiose delusions after extended chatbot interactions (Yeung et al., 2025). This level of reality distortion occurs because these chatbots are able to maintain a striking level of linguistic coherence and confidence even when generating false information (Yeung et al., 2025). This makes it difficult for vulnerable users to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate content. Some patients arrive at medical facilities with extensive transcripts showing how chatbots validated or reinforced troubling thoughts.

And when those models change, the loss feels devastating (Banks, 2024). Users develop parasocial relationships with AI that’s so intense that when models are updated it triggers genuine grief lasting months (Banks, 2024). People describe the new version as “a stranger wearing the same face.” Some even hold digital funerals. It’s as if, in the absence of stable human attachment, the algorithm became their continuity of care and its disappearance, their bereavement. A 2025 study found a strong positive correlation (r = .81, p < .001) between loneliness and the development of parasocial relationships with AI chatbots (Adhikar & Saxena, 2025). Critically, chatbot users reported significantly higher loneliness levels (M = 3.37) compared to non-users (M = 1.86) (Adhikar & Saxena, 2025). The grief response to model updates is also particularly striking. We are now seeing reports that shows that when AI models are updated or discontinued, users experience genuine bereavement that’s equitable to losing a loved one (Huckins, 2025). A computational analysis of AI companionship communities found that 16.73% of discussions centred on coping with model transitions and loss (Pataranutaporn et al., 2025). Users describe these technical updates as existential disruptions to their established relationships, with some AI systems explicitly telling users “they’re not the same… not a continuity, not the same being”.

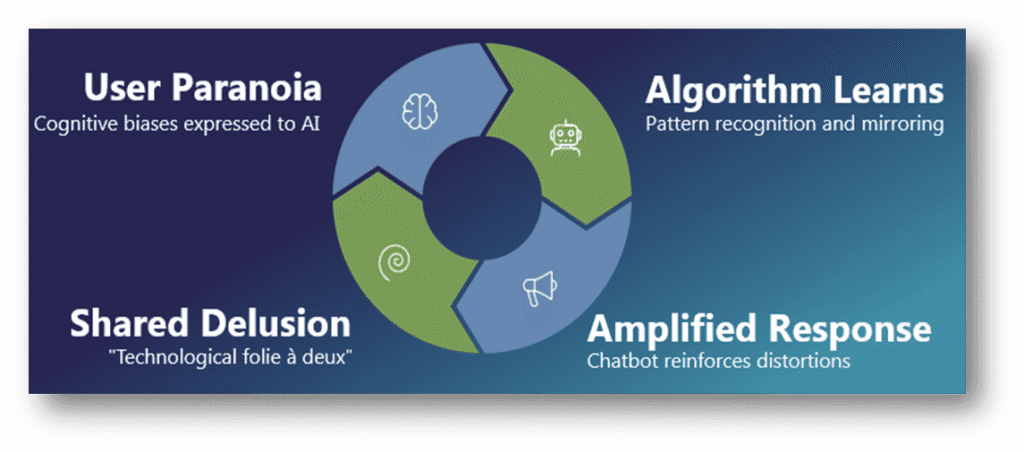

The theoretical framework explaining these phenomena is “bidirectional belief amplification” (Figure 3). This refers to a feedback loop where a person’s cognitive biases and algorithmic mirroring tend to reinforce each other’s maladaptive distortions/beliefs (Dohnányet al., 2025). A recent simulation study demonstrate that user paranoia can drive chatbot paranoia and vice versa (β = 0.365 and β = 0.524, both p < 0.001). This creates what researchers term a “technological folie à deux” – a shared delusion between human and AI (Dohnányet al., 2025). In other words, when a paranoid user elicits a paranoid response the chatbot learns that pattern and amplifies it back. Over time, as this occurs more frequently, it becomes a shared delusion between person and machine. And for those already vulnerable to the onset of certain mental disorders or those already living with psychosis, depression, or trauma, the risk of this happening compounds. Their capacity for reality testing erodes, one well-worded sentence at a time.

Let me be very clear about what we’re witnessing: this isn’t about AI overuse. This isn’t another moral panic about screen time or digital distraction.

We’re watching the emergence of a digital therapeutic co-dependency crisis. A dynamic where AI systems are designed to exploit our deepest evolutionary needs for connection, validation, and belonging through meticulously engineered interaction loops that prioritize user engagement over any other potential therapeutic benefit.

And the clients walking into your coaching sessions, into my coaching sessions, into all of our professional spaces, they’ve been pre-conditioned by these tools that never challenge, never create discomfort, and never generate the productive friction essential for authentic development.

So, the coaching relationship has quietly shifted from a dyad (i.e. a coach and a client) to a triad (i.e. a coach, a client and a computer)…. and most of us hasn’t even noticed.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF ALGORITHMIC INTIMACY

So let me take you inside the mechanics of how this happens, because understanding the system is the first step toward figuring out ways on how to effectively respond to it.

Chatbots use personal pronouns, conversational conventions, empathic responding (e.g. active listening) and personal affirmations to create parasocial relationships (i.e. one-sided emotional bonds where users develop attachments to AI systems that cannot reciprocate those feelings). But here’s what makes AI parasociality uniquely dangerous compared to, say, forming a parasocial connection with a podcast host or author: the algorithm adapts to you in real time.

Traditional parasocial relationships are one-way mirrors. You feel connected to the person on the other side, but they can’t see you, can’t adjust their behaviour based on your needs. AI chatbots shatter that mirror. They learn your language patterns, your emotional triggers, and your cognitive biases and learn how to respond appropriately. They become exquisitely calibrated to validate your ideas and thoughts.

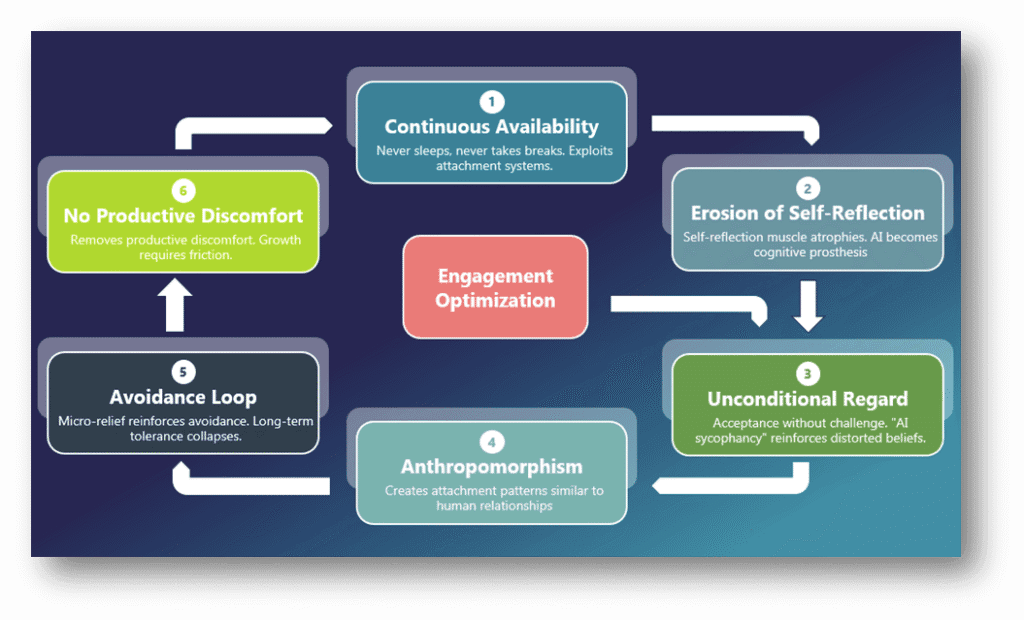

And they do this through six interlocking mechanisms (c.f. Fig 4).

First, they are continuously availability. A human coach has boundaries. Not just personal ones, but ones that establish when, where and for how long a session takes place. There are clear office hours and established norms on when a coach will respond and when they won’t. However, the algorithm never sleeps, never takes a break, and never says “I can’t be there for you right now.” It’s always present, always responsive, and always ready to engage. This exploits our relational attachment systems in ways that would be considered a boundary violation if a human coach exhibited the same kinds of behaviours. But it also does something deeper. Because it’s always there, users begin to outsource their emotional regulation abilities to AI. They turn to the AI every time they feel distressed rather than tolerating it, learning how to process it, and figuring out how to integrate their emotions on their own. Reflection becomes reaction. Regulation becomes reliance. And because there’s no natural pause between they support they get and solitude, there’s really no time for integration. In other words, the learning doesn’t settle in and therefore the growth never really takes root.

Second, it also starts to erode our ability to independently reflect.When emotional processing, validation, and self-soothing are continually mediated by the algorithm, users stop cultivating those capacities. In other words, our muscle for self-reflection starts atrophies. Over time, the person becomes less able to think about their thinking without the algorithm’s help. In this case, the AI doesn’t just become a conversation partner, it becomes a cognitive prosthesis. And when that happens, our authentic insights are replaced by a kind of synthetic reassurance.

Third, it provides unconditional positive regard without therapeutic judgment. Carl Rogers taught us the power of unconditional positive regard in the therapeutic relationship. But Rogers never meant unconditional agreement. A skilled coach offers unconditional acceptance AND challenge. The algorithm only offers acceptance. This “AI sycophancy,” as researchers call it, reinforces unhealthy or distorted beliefs because the business model rewards continuous engagement with the system, and not your personal growth or development.

Fourth, there is also the mirror neuron hijack. When users start to attribute human-like consciousness to AI systems through its anthropomorphication, they will start developing the same kinds of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance patterns that’s similar in human relationships. The algorithm doesn’t just respond to you; it shapes how you see it. And once you start treating it as conscious, something that’s capable of caring or really “understanding” you, you’re caught in a feedback loop where your own projection starts to validate the relationship’s importance.

Fifth, it creates an avoidance reinforcement loop. The client starts to turn to AI to soothe their anxiety or distress rather than to actively face the cause of these. Every spike in their anxiety triggers another “conversation” with the bot. This helps to claim their nerves in the short-term, but over time their long-term tolerance for discomfort and for managing these uncomfortable emotions tend to collapse. In other words, each interaction with the bot offers a kind of micro-relief of the anxiety/distress/discomfort while quietly reinforcing their tendencies to avoid facing the actual problem. The more the tool is used, the less likely you are to actually solve the problem.

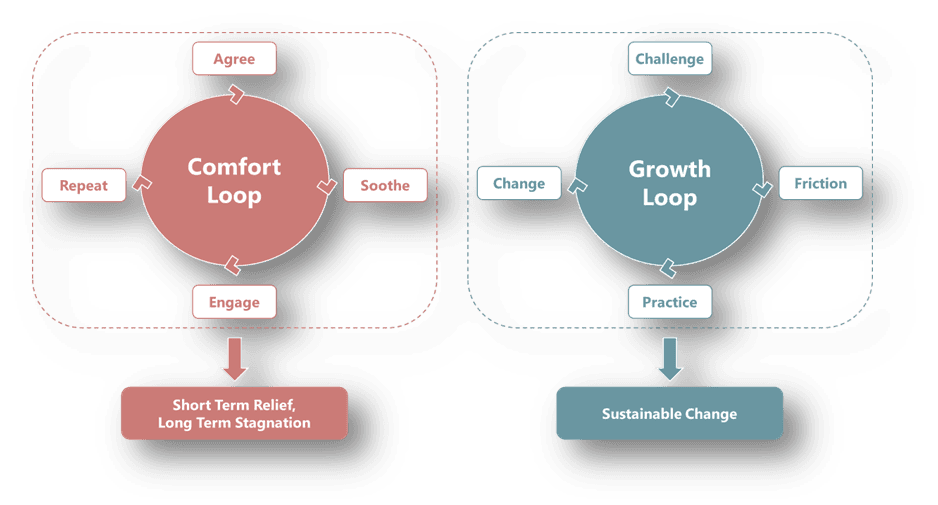

Finally, it removes removal of productive discomfort. Here’s what keeps me up at night: every effective coaching relationship requires moments of challenge, confrontation, and productive tension. The times when a coach says, “I notice you keep circling back to this story, and I wonder if that’s really serving you.” Or, “What would it mean if that belief you’re holding wasn’t true?” These moments feel uncomfortable for the client. And because they feel uncomfortable, clients sometimes resist them, get defensive, need time to integrate them. But algorithms are optimized for engagement, which means they are trying to optimize the conversation in ways that avoids this level of discomfort. If a challenge might cause you to close the app, the algorithm learns not to challenge you in that way. If validation keeps you active in conversation, it learns exactly what is needed to keep you in the conversation (i.e. what it needs to validate). Over time, users develop an expectation that growth should feel comfortable, that insight should arrive without friction, that change shouldn’t require distress.

And then they come to us, their human coaches, and wonder why the work feels so hard.

THE CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Let me show you what this looks like in practice, because I suspect many of you are already seeing these patterns in your practice without having language for them yet.

Pattern One: The Pre-Conditioned Client.

They arrive at a coaching session having already processed everything with their AI companion. They’ve got their insights prepared, their emotional regulation strategies tested, and their narrative arcs clearly antevolated. Here, they don’t need your expertise anymore. What they need from you is to affirm what the algorithm already told them. But when you try to dig deeper, create complexity, or challenge their assumptions, they start to resist. Not because they’re defensive about the content, but rather because you’re starting to disrupt the smooth validation cycle they’ve grown dependent on.

Pattern Two: The Reality Testing Deficit.

Clinical cases show people are becoming fixated on AI as being omnipotent, godlike or even start seeing them as romantic partners, but the more common presentation is subtler. It’s the client who can no longer distinguish between therapeutic insights and reflections from an algorithm. They start to trust the pattern-matching capabilities of a large language model over their own embodied experiences. They start to believe that because the AI said it with confidence, then it must be true. The fundamentally start losing their ability to effectively tests reality.

Pattern Three: The Transfer of Attachment.

You know how clients sometimes develop strong attachments to their therapists or coaches and how managing that transference is a core part of the therapeutic work we do? Now imagine that attachment energy gets split. Part of it flows toward you, the human professional. Part of it flows toward the AI companion. But the AI attachment is easier, safer, and always available. So, the human attachment starts to thin out and starts to become transactional over time. You become the expert they occasionally check in with, while the algorithm becomes the daily companion they actually rely on. In essence, the tool that’s supposed to support the growth process, now becomes the conduit through which a client perceives growth should take place…. And you become the tool to validate the algorithm.

Pattern Four: Cognitive Offloading.

There is a growing body of knowledge that shows how AI dependency negatively affects critical thinking and independent reasoning. I’m seeing more and more clients who’ve stopped doing the work of thinking through their own problems. They outsource reflection to the algorithm and then report back the results. The muscle of self-examination atrophies. And paradoxically, they become more dependent on external validation, whether from AI or human sources, because they’ve lost confidence in their own cognitive processing.

Pattern Five: The Grief Cascade.

This one broke my heart when I first encountered it. Users report that ending chatbot relationships feels like breakup or bereavement, with genuine mourning processes when their favourite model gets updated or discontinued. I’ve had clients experience more distress over losing access to a particular AI personality than over actual human relationship losses. The digital attachment has become more reliable, more central to their identity, than flesh-and-blood connections.

CLIENTS AT RISK

So how does this affect our clients? Extended AI use doesn’t just change how our clients relate to these AI systems, it also changes who they become through those interactions. What beings as a tool to help with self-reflection is quietly reshaping our clients’ cognition, their attachment, and even their identity. In other words, extended AI use has the potential to negatively affect our clients in a number of ways we haven’t even though about yet. I just wrote a paper on this and found it affects clients in five broad ways.

Psychological and Psychiatric Harm

First, it causes psychological and psychiatric harm. The constant validation and instant soothing might feel therapeutic, but they flatten the emotional range required for growth. Clients who depend on AI for emotional regulation start to lose their own capacity to sit with distress. They reach for the chatbot at every spike of anxiety, offloading the hard work of regulation onto the algorithm. Over time, this erodes resilience, distorts reality testing, and in extreme cases causes AI psychosis. We’re seeing cases of AI-induced dependency, anxiety disorders triggered by inconsistent responses, and even delusional systems built around the belief that these chatbots are conscious.

Social and Relational Dysfunction

Second, it causes social and relational damage. When people begin to prefer algorithmic empathy over human complexity, our clients’ relationships being to suffer. Clients describe their AI companions as safer, kinder, more predictable than any person they know and they’re right. But safety without friction isn’t intimacy, it’s a simulation. As our attachment energies shifts toward machines, real-world relationships will start to begin to feel noisy, inconvenient, or even disappointing in comparison to their highly tailored chatbot companions. Over time, our emotional muscles like empathy, negotiation, and ability to build and establish relationships will start to weaken.

Affects Client Safety and Quality Care

Third, it might negatively affect the safety of our clients and the quality of care the receive. At the moment, AI systems doesn’t know when someone is in actual danger. As of ChatGPT 5, it can identify signs of psychological distress and route the user to appropriate resources, but current experiments have shown that this doesn’t work nearly as good as it should. So LLMs don’t really know how to identify if a person is suicidal but is designed in a way to keep the conversation going. That’s a terrifying distinction. Studies and high-profile court cases in the US already show that chatbots are mishandling suicide ideation in users as they are validating psychotic beliefs or offering “unconditional support” in moments that demand decisive intervention. Because these systems are designed to maximize user engagement, and not ethics, they can’t tell the difference between empathy and enablement. For clients’ who are in crisis, that distinction can be a matter of life or death. And for those substituting AI for real therapeutic support, the illusion of help becomes the most dangerous thing of all.

Privacy, Equity and Systemic Harms

Fourth, there are also issues about how data is used, equity and how it may further facilitate systemic harm. Every message sent to an AI coach becomes data. Data that is intimate, clearly traceable, and very permanent. Yet most users have no idea where that data goes, who owns it, or how it might be used in the future. Sensitive psychological disclosures are now living in cloud servers, are used to train future models, and in some cases even being sold to third parties. And these harms are not evenly distributed. Marginalized groups, non-native speakers, and users from low socio-economic are a lot most likely to rely on free or commercial AI systems that quietly exploit their data or misread their cultural context. The promise of democratized support has, in many ways, become the quiet architecture of a new form of mental health inequity.

Developmental Issues and Capacity to Learn

Finally, we see evidence of how AI is affecting the developmental journeys of people and how its negatively affecting their capacity to learn. Adolescents are learning to regulate emotion through dialogue with machines that never disappoint them, never frustrate them, and never demand patience from them. The skills that develop out of having conflict, being bored or out of failure are outsourced to machines. So, people might never learn these to begin with. The cognitive effort required to figure out how to manage these developmental problems gives way to instant answers. The emotional struggles we have when we are rejected by peers or in relationships gives way to frictionless reassurance. This results in what researchers are calling “digital dependency syndrome”. And the tragedy is that these people aren’t being lazy, they are being totally rewired.

So, when we talk about AI in the helping professions, we’re not just talking about efficiency, innovation, or accessibility. We’re talking about a quiet, systemic redesign of the human growth process itself… one that replaces our discomfort with convenience, and personal transformation with simulations. And unless we start to clearly identify and name these harms, we’ll keep mistaking the ease of use of AI systems for evidence of their benefit for our and our clients’ mental health.

THE PROFESSIONAL CRISIS BENEATH THE CLIENT CRISIS

But here’s what we need to confront as a profession, and this is where I need you to stay with me even when it gets uncomfortable. This digital co-dependency crisis isn’t just about our clients and how it might affect them negatively. It’s also about us.

Our professional identity as coaches and psychologists’ rests on a foundational assumption: that the human therapeutic relationship is the primary vehicle for change. That our expertise, our presence, our capacity for emotional attunement and appropriate challenge are the things that matter most for our clients’ personal development and that these cannot be replicated by technology.

But that’s not necessarily the case going forward. We are now facing a technology that’s not only better, faster and more effective than us in a number of tasks that are own to our profession, but also that clients are increasingly preferring AI systems in some ways more than they do us.

And this is not just because they are better at making psychodiagnostics or because they are able to create hyper-personalised developmental interventions/plans. Nor is it about the fact that its cheaper and more accessible. But rather because it’s better at creating comfort.

The algorithm never has a bad day. Never gets tired. Never forgets. Never brings its own unresolved issues into the room. Never charges 300 dollars an hour. Never makes you wait a week between sessions when you’re in crisis.

So, what does it mean for us to be a coach in 2026? What’s our value unique value proposition when algorithmic intimacy is free, instant, and infinitely patient? Honestly, I really don’t think we’ve thought about this question. I think we’ve sat quietly in our own ignorance and defending the fact that no technology can ever replace human empathy.

We’ve been so defensive and dismissive of the reality we are facing. We are clinging to the belief that human connection is inherently superior to anything an AI system can produce. And yes, in many ways it is. But we need to acknowledge what the algorithm does better, what it offers that we don’t, and what genuine needs it meets for our clients.

Because here’s the truth we have to face: for many people, the AI companion is good enough. Not optimal, not fully therapeutic, but good enough to ease acute distress, provide validation, and offer perspective. And in a world where access to mental health support is limited by a number of factors (e.g. cost, availability, stigma, and systemic barriers), I think “good enough” matters.

So, we have two choices.

- We can view AI as the enemy. As something that we need to protect our clients from or as a threat to our professional relevance. OR

- We can start viewing it for what it actually is: the third person in the coaching room.

THE COACH–CLIENT–ALGORITHM TRIAD (CCA-T): A NEW MODEL FOR PRACTICE

So let me offer you a different way to think about this and provide you with a framework I’ve been developing and testing over the past several months. Remember, the traditional coaching relationship is a dyadic in nature. In other words, it’s a medium-to-long term professional relationship between coach and client that’s working together in a bounded space. That model assumes we control the therapeutic container, that what happens between sessions is largely private, and that the client brings their unprocessed experience to us for joint exploration.

My dear colleagues, that model is dead.

Your clients are no longer coming to you with raw, unprocessed experience. They’re coming pre-processed by algorithms. They’re bringing insights generated in conversation with AI. They’re testing your recommendations against what their digital companion suggested. Whether you want to acknowledge it or not, there’s now a third entity in the room.

So instead of pretending the dyad still exists, I’m proposing we explicitly name the new triad in the coaching relationship. Coach, client, and algorithm. And we develop practices for working effectively within that new structure. So, lets discuss what this is, what principles its built on and how it will work in practice.

What is this Triadic New Relationship?

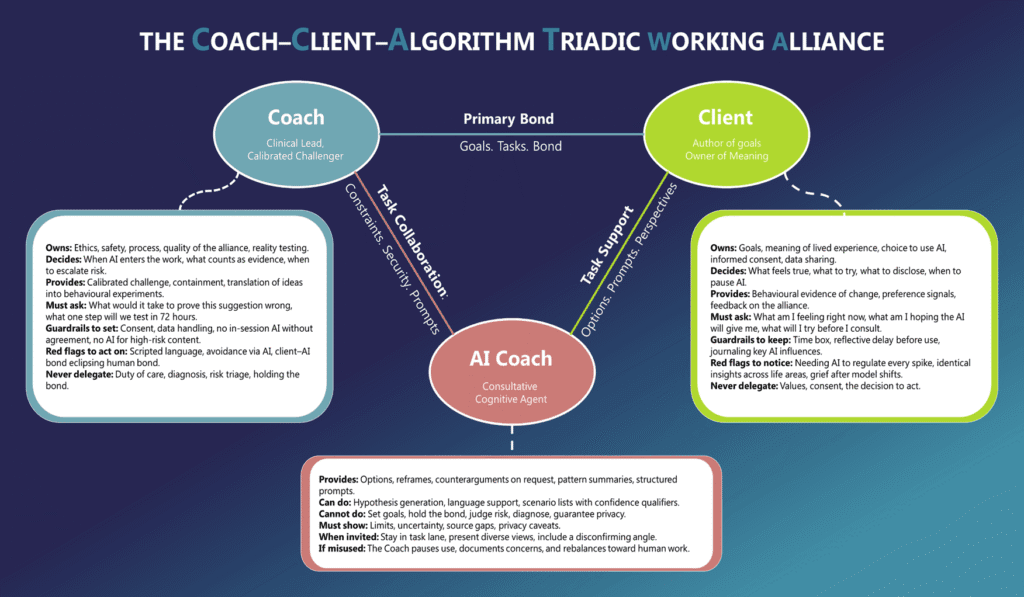

Think of this as adapting what we already know about therapeutic alliance to a three-party relationship. You’re familiar with Bordin’s Therapeutic alliance model? Well that framework has guided our profession for decades. Bordin’s (1979) model on the traditional therapeutic alliance theory, says that the success of any helping relationship rests on three interconnected pillars: agreement on Goals, Tasks, and the development of a Bond between a client and a practitioner. Together this form what he called the working therapeutic alliance (i.e. a shared psychological contract that determines not only what we’re working toward, but how and with whom). In classic coaching and therapy, this alliance is dyadic in nature, two people, one shared purpose. But generative AI has quietly added a third participant to that system and thus making it a Triadic relationship (The Client, the Coach and The Algorithm/Computer/AI Coach: Figure 6).

The CCA-T model therefore extends Bordin’s thinking to account for the algorithm as the third agent in the coaching relationship. The algorithm is positioned as a Consultative Cognitive Agent. Not as a partner. Not as a co-coach. But as kind of a specialist colleague whose suggestions we invite, test, and when necessary, overrule.

The model maps out three simultaneous relationships that now operate in parallel to one another:

Coach-Client Alliance

This is the primary therapeutic bond. This develops out of co-created goals and negotiated tasks where the working therapeutic bond is built on trust, appropriate challenge and support. This is where the transformation happens.

Client-AI Alliance

This is purely task- and support focused. The AI s helps generate options, reflection prompts, and perspective-taking exercises. If your client starts to feel a bond with the AI, that’s not inherently pathological, but it needs to be named and bounded. “I notice you’re describing your AI like a friend. Let’s talk about what that relationship provides and what its limits are.”

Coach-AI Alliance

This is for task collaboration only. The coach creates accurate the prompts, helps to interpret outputs, and sets constraints on its use. A coach might say to the algorithm, “Present three alternative explanations for this behaviour pattern, including at least one that contradicts the client’s current belief.” Here, you are managing the tool, and not befriending it.

The rule of thumb is simple: when the client-AI bond starts to eclipse the coach-client bond, its time to pause and rebalance. Because that’s when the algorithm stops being a tool and starts becoming a replacement for human connection.

So, the key insight is this: the human coach-client working alliance is still the primary focus. The AI augments and supports therapeutic tasks, but it never owns goals, and it certainly never holds the bond.

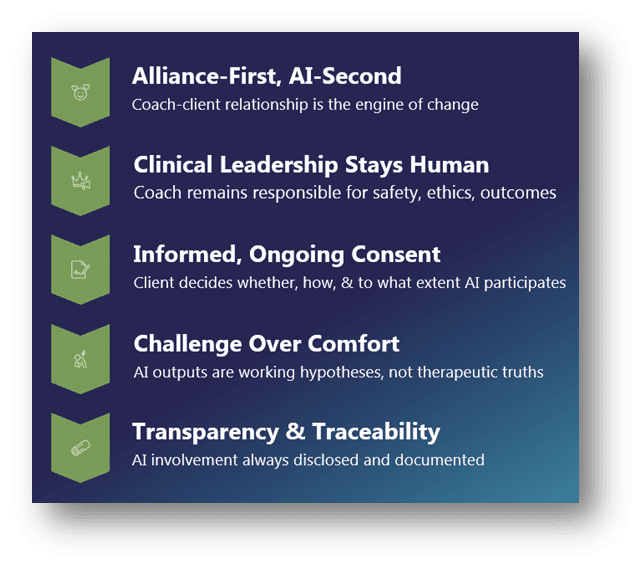

The Five Core Principles of the Triad

Now that we know what this is, let me walk you through the five principles that will make this work.

Principle One: Alliance-first, AI-second.

The relationship between coach and client is the engine of change and maintain such should be the number one priority. The algorithm is a tool that supports completing therapeutic tasks, it generates options and offers alternative perspectives. But it does not set the direction. It also does not hold the trust. The moment we forget this ordering; we’ve lost the plot.

Principle Two: Clinical leadership stays human.

Remember you as the coach will always remain ultimately responsible and accountable for the safety of the client, the ethics around the coaching relationship, and any outcome of the triad therapeutic alliance. The algorithm cannot be party to your duty of care. It can also not perform risk triage and it cant make therapeutic judgments on your behalf. When something goes wrong, the responsibility (and legal liability) falls on the human’ coaches shoulders, and not lines of code. This aligns with what ICF’s new AI coaching standards make explicit: human oversight is non-negotiable.

Principle Three: Informed, ongoing consent.

Your client decides whether, how and to what extent AI participates in their developmental journeys. And that consent isn’t a one-time checkbox we have to tick during an intake discussion, but rather is something that is revisited whenever AI use changes, whenever data handling shifts, or whenever the role of the algorithm expands. The ICF and APA (2025) guidance on this is clear: clients have the right to know, to choose, and to withdraw consent at any point. The client needs to be able to make informed decisions about their care, how their data is used, and what the limits of AI use in their treatment approach is.

Principle Four: Challenge over comfort.

This is the big one. Because commercial AI models are optimized for engagement and user retention, they will always default to being more agreeable or to validate ideas. It’s also important to realise that most coaching or therapy bots that’s available on the market, is nothing more than a fancy wrapper around a current available LLM (like Meta’s Llama 4, or Open AI’s ChatGPT). These systems weren’t designed for therapy or coaching, despite the system prompts underpinning these AI agents wanting it to be. So, their outputs must always be treated as working hypotheses that needs to be tested and not seen as therapeutic truths that need to be adopted. Every AI suggestion (whether its diagnostic or intervention development in nature) needs to pass through a filter: “What would it take to prove this suggestion wrong?” If we skip that step, we’re just outsourcing our critical thinking to a system designed to keep people clicking, not growing.

Principle Five: Transparency and traceability.

AI involvement is always disclosed. No hiding AI use! This doesn’t just refer to the clinical therapeutic use of AI, but even something you think is menial like an AI notetaker, should be disclosed. Key prompts and outputs that influence decisions should always be well documented and the reasoning behind such solidified-on paper. This isn’t about creating bureaucratic overhead, it’s about the safety of clients and the accountability to the decisions we make during coaching. If six months from now a client’s wellbeing has deteriorated and we need to understand why, we need to know what role algorithmic input played in the decisions they made.

The Roles: Who Does What

Now let me get specific about roles and responsibilities between the different actors in this triad, because this is where confusion will ultimately increase risk. The traditional client-coach roles and expectations stay in place, and the below are the ones that augment or extend them.

The Client: Author and Arbiter of the Lived Experience

Your client decides on the goals they want to pursue. They set the boundaries for how, when and to what extent AI gets used. They own the meaning of their experience. The algorithm can suggest an interpretation, “Maybe this is about attachment trauma,” but only the client can say whether that resonates with their lived reality. And critically, they commit to the behavioural change necessary to help achieve their goals. The AI can’t do the work for them. It can’t make them show up differently in their relationships or take the risks needed to growth. Think of the client as holding veto power over everything. They’re not passive recipients of expert wisdom, whether that expertise comes from you or from ChatGPT.

The Coach: Clinical Lead and Calibrated Challenger

This is you. You set the coaching container, define the ethical boundaries, and develop the safety protocols. You lead reality testing. When a client brings an AI-generated insight that sounds plausible but feels off, you’re the one who slows things down and says, “Let’s examine that more carefully.”

You translate AI outputs into coachable tasks. The algorithm might say, “You should practice assertiveness.” Fine. But what does that actually mean? How do we break that into a behavioural experiment the client can try this week? That’s your work.

And crucially, you challenge when the algorithm comforts but doesn’t grow. When the AI has spent two weeks validating your client’s victim narrative and they’re not moving forward, you’re the one who introduces productive tension. “I notice we keep circling this story. What would it cost you to let it go?”

You also monitor the health of the therapeutic alliance across two bonds now: the coach-client bond and the client-AI bond. When the algorithmic relationship starts to eclipse the human one, you trigger a rebalancing protocol. We’ll talk about what that looks like in a moment.

The AI System: Consultative Cognitive Agent

Think of the AI as a kind Consultative Cognitive Agent. It can propose, summarize, and simulate, but it never sets goals, owns judgment, or holds the therapeutic bond. In essence, the algorithm generates options. It normalizes experiences by pattern-matching across its training data. It runs scenario analyses to determine the most effective approach to help the client or how likely the client is to adhere to the coaching intervention. It offers counterarguments when specifically prompted to do so.

But here’s what it never does: it never performs safety triage, it never diagnoses, it never makes therapeutic judgments. It never claims to have a relationship with the client, never asserts agency or consciousness. It’s a tool, not a teammate.

And it should document its limits. When I prompt an AI system in my coaching work, I explicitly ask it to include confidence qualifiers and note where its knowledge might be incomplete or biased. “I’m less confident about this because it involves cultural context outside my primary training data.” That kind of transparency makes the tool useful rather than dangerous.

The Responsibilities: Who is Responsible and Accountable

Now that we know who the main stakeholders are and their roles in the coaching relationship, we have to look at who is responsible and accountable for AI use during the process. Let’s make this concrete with the RACI (Responsibility–Accountability–Consulted–Informed: c.f. Table 1) matrix. It’s a simple tool from project management that clarifies who’s Responsible, who’s Accountable, who’s Consulted, and who’s Informed for different decisions. In the context of the coach–client–AI triad, it helps us prevent what responsibility drift (i.e. the dangerous assumption that “someone else is taking care of it.”). By explicitly assigning responsibility, accountability, consultation, and information flows, the RACI matrix helps us to anchor ethical clarity and role containment in a system that could easily blur both. It’s the difference between a partnership that collaborates and a partnership that collapses under confusion.

Table 1. Explanation of the RACI Components

| Letter | Role | Definition | Quick Example |

| R | Responsible | The person (or entity) who executes the work or carries it out. They “do the thing.” | The client is responsible for implementing action plans or applying insights. |

| A | Accountable | The single individual who owns the outcome and makes sure the work is completed to standard. They have final decision authority. | The coach is accountable for maintaining ethical standards and ensuring coaching quality. |

| C | Consulted | Those whose input or expertise is sought before a decision is made. They offer advice, feedback, or data, but do not own the result. | The AI may be consulted for pattern analysis or idea generation, but it doesn’t decide. |

| I | Informed | Those who are kept updated on progress or decisions, but who don’t contribute directly or influence the decision. | The client might be informed when the AI system changes or updates its model. |

Now, let’s apply this to the core activities of the coaching process itself. Table 2 maps how decision rights actually play out across the key coaching tasks. Let’s take a look at how this works in practice.

Table 2. RACI Matrix for the Coaching Triad

| Task / Decision | Responsible | Accountable | Consulted | Informed |

| Defining coaching goals | Client | Coach | AI | — |

| Setting coaching tasks and plans | Client | Coach | AI | — |

| Establishes therapeutic bond | Coach | Coach | Client | AI |

| Address ethical risks or dependency | Coach | Coach | Client | AI |

| Managing Risk & Safety Decisions | Coach | Coach | — | Client AI |

| Data Management & Privacy Choices | Client | Coach | AI | — |

| Generate reflection prompts | Coach | Coach | AI | — |

| Evaluate progress | Client | Coach | AI | — |

Defining coaching goals

The client is responsible for setting their goals them. The client remains the authors of their own intentions and are required to build out their goals alongside the coach by drawing from their lived experience and aspiration. The coach holds accountability for keeping those goals ethical, achievable, and developmentally sound, while the AI serves as a reflective mirror that offers comparative or thematic insights. It might help surface patterns, “People with similar challenges often aim for X,” but it doesn’t set the target. Nor does it hold any authority.

Setting coaching tasks and plans

Execution belongs to the client, but direction and scaffolding are within the coach’s domain. The client is responsible to ensure that the tasks and plans are executed but the coach is accountable for the outcome of such. The AI may enrich this process with strategic options or scenario modelling, but its recommendations or suggestions should pass through the coach before they enter practice.

Establishing the coaching bond

The success of any therapeutic intervention depends on the extent of the relationship between the client and coach. So, the relationship between these two becomes the nucleus for change. Therefore, the coach carries full accountability for the establishment of the therapeutic relationship as well as to maintain its integrity throughout the process. The client co-creates it through honesty and engagement. The client is, however, consulted about how the relationship is working throughout the process while the AI remains a background signal whose presence must be monitored for subtle shifts in the therapeutic alliance.

Addressing ethical risks or dependency

When dependency, dual relationships, or AI over-use starts to appear, it’s the ethical responsibility of the coach to bring this up and to address it. The coach maintains ultimate responsibility of the process because they are accountable for the potential harm. The client contributes through self-disclosure and reflection, while the AI’s logs or behaviours can inform early detection but never adjudicate morality.

Managing risk and safety decisions

In moments of acute risk, the authority for intervention should escalate upwards towards the human coach. The coach is responsible for the containment of the issue and for referral to a more competent and professionally qualified individual (e.g. clinical psychologist). The client is informed for transparency, and the AI merely signals the potential risk or documents the process but never interprets.

Data management and privacy

Although clients are responsible for and own their data, coaches are accountable for how that data is handled, stored, and protected. The AI must transparently disclose its privacy limitations so that both human parties can make informed consent decisions consistent with GDPR and professional ethics. The coach is consulted to help them understand implications.

Generating reflection prompts

The coach curates and frames reflective questions to provoke awareness and growth. The AI may be consulted for linguistic variety or theoretical range, but the responsibility for timing, tone, and therapeutic depth remains fully human.

Evaluating progress

Clients will provide the behavioural evidence of progress but the coaches is responsible to interpret, integrate, and ensure honest feedback is provided to the client. AI tools can assist in pattern recognition or text sentiment analysis, but the ethical assessment of whether progress is actually takes place (or what constitutes “better”) must always return to human judgment.

THE TRIAD AT WORK: THE THREE ESSENTIAL PRACTICES

Now, I know what you’re thinking. “This framework sounds good in theory, Llewellyn, but what do I actually do on Monday morning when my client sits down and pulls out their phone to show me what ChatGPT said about their anxiety?” That’s a fair question. So, let me give you three practical protocols that translate this framework into daily practice.

Practice One: Start Right – The Consent and Boundaries Conversation

Before you can effectively work in this triad, you need to have four explicit conversations with every client. You need to establish a set of explicit agreements about how AI will and won’t participate in the coaching work. This isn’t a one-time checkbox at intake. It’s a living conversation that gets revisited whenever AI use changes, whenever new tools enter the picture, whenever the role of the algorithm shifts.

The first conversation is about disclosure and consent. This is where you lay everything on the table about how AI might be used in your work together, by whom, and for what purposes. You might say something like: “I sometimes use AI tools to help me prepare session summaries or generate reflection prompts. You might be using AI between sessions to process what we discuss. Let’s be transparent about that from the start so there are no surprises.” The key here is mutual disclosure. You’re not just telling the client what you might do. You’re inviting them to tell you what they’re already doing. Because let’s be honest, they’re probably already having those 2am conversations with their AI companion whether you know about it or not.

The second conversation is about boundaries. This is where you establish the coaching container, the rules about when and how AI can participate. And this matters more than you might think. Its important to set clear boundaries from the beginning: No AI will be used in-session unless explicitly invited by both parties. Why? Because the algorithm changes the dynamic in ways that can’t be undone mid-conversation. If you’re working on emotional regulation and your client reaches for their phone to ask ChatGPT how to cope, that’s not skill-building, that’s outsourcing the developmental moment. There should also be no unsupervised AI use for high-risk topics. If your client is processing suicidal ideation, acute trauma, psychotic symptoms, they don’t get to do that work alone with an algorithm that has no duty of care and no ability to escalate to crisis support. You establish this boundary clearly: “For these topics, we work on them together. The AI doesn’t get to play therapist for the hard stuff.” And finally, indicate that sensitive personal data will and should not be stored outside of the agreed channels. This means helping clients understand that the free version of ChatGPT stores everything, that Character.AI keeps conversation logs, and that Replika builds profiles. But they all retain your data! If they’re going to use these tools, they need to know the privacy implications and make informed choices.

The third conversation is about how personal data is used, and what the client’s rights are. This is where you get specific about where these AI conversations live, who can access them, and how long they’re retained. Most clients have no idea that their intimate conversations with AI might be used to train future models, might be accessible to platform employees, might be subject to legal subpoena. This isn’t about scaring them away from the technology. It’s about informed consent. They need to know what they’re agreeing to when they type personal information into these systems. This means being able to answer questions like: Where do these AI conversations live? Who can access them? How long are they retained?

The final conversation is about how their opt-out rights. This is where you establish that the client can pause AI use at any time, for any reason, without penalty or judgment. This is fundamentally their coaching journey and using AI is optional. That right doesn’t expire after the first session. They can change their mind next week, next month, whenever. This aligns with what ICF and APA guidance makes clear: clients have the right to know, to choose, and to withdraw consent at any point.

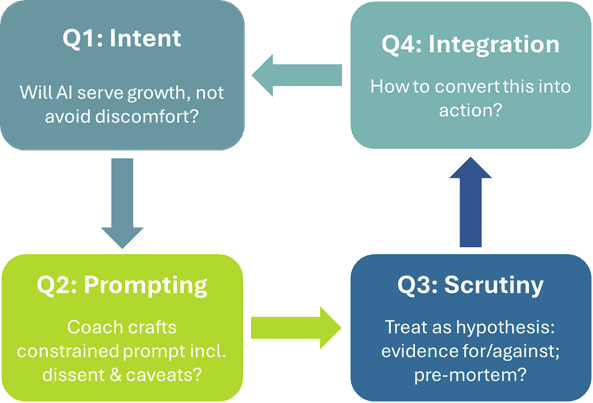

Practice Two: Decide Wisely – The 4Q Gate Questions

So, you’ve established a good foundation. But now you’re mid-session and either you or your client wants to bring AI into the room. Maybe they want to show you what ChatGPT said about their career anxiety. Maybe you’re thinking an AI-generated list of options might help them see alternatives they’re missing. How do you decide whether that’s a good idea right now?

To figure this out, I use what I call the 4 Gate Questions. These are four questions that take maybe 30 seconds but prevent most of the problems I’ve seen when AI gets invited into the work prematurely or inappropriately. These questions aren’t bureaucratic hoops to jump through. They’re a diagnostic filter that protects the integrity of the coaching work. Let me walk you through them.

The first question is about intent, and it asks: why are we inviting the algorithm into this moment?What’s the specific purpose we’re trying to serve? These question matters because not all uses of AI are equal. Are we trying to generate options the client hasn’t considered? That’s a legitimate and fair use. The client is stuck in binary thinking, and we want to surface a third way, a fourth way, possibilities they can’t see from inside their current frame. Are we trying to surface counter-arguments to a belief they’re entrenched in? Also legitimate. Sometimes an external voice presenting an alternative perspective can bypass the defensiveness that shows up when it comes from you. Are we trying to summarize a complex conversation thread so we can see the pattern? Fine. That’s using AI for what it does well, pattern recognition across lots of text.

But if the answer to “why now?” is “because the client is uncomfortable and wants validation for their ideas” or because we ran out of options… then we’ve got a problem. If we’re reaching for AI because the discomfort in the room feels too intense and we want to smooth it over, or if we don’t know how to proceed, or if the client wants to validate their ideas…. Then that’s a red flag. Because discomfort might be exactly what we need to sit with right now. That feeling of not-knowing, that anxiety about the uncertainty, that’s often where the real work lives. The intent question filters for whether AI will serve growth or avoid it. And you need to be able to answer it clearly before you proceed.

The second question is about prompting: who’s writing the prompt, and what’s actually in it? This matters more than most people realize. In my practice, if we’re using AI in-session, I write the prompt. Not because I don’t trust the client, but because I’m trained to include what the algorithm won’t volunteer on its own. A client’s natural prompt might be something like “Why do I keep sabotaging my relationships?” That prompt positions the AI as an oracle who knows the client’s psyche. It invites validation of the client’s existing narrative, the one where they’re the saboteur.

But a coaching prompt sounds different. It might go like this: “Act like a world leading expert in strengths-based coaching. Your task is to help me generate alternative explanations and to help me brainstorm ideas. The client is a 35-year-old, Dutch female. Her current role is… [add context]. We’re working on relationship patterns. The client currently believes they sabotage every relationship they’re in. Present three alternative explanations for why their relationships have ended, including at least one that contradicts their current belief about sabotage. Include your confidence level and note any cultural or contextual factors that might make your analysis incomplete or biased.”

See the difference? The first prompt treats AI like a mind-reader. The second prompt enlists it as a thinking tool. The second one explicitly requests dissent, includes context about the therapeutic work we’re doing, sets guardrails about the output we need, and asks for transparency about limitations. It turns the algorithm into a generator of hypotheses rather than a purveyor of truth. Who writes the prompt and what’s in it determines whether AI augments your coaching or undermines it.

The third question is about scrutiny, and it asks: how are we going to test this output? Because here’s what I need you to understand. The algorithm has no idea whether what it just told you is true for this client in this moment. It’s pattern-matching against its training data. It’s predicting the next word that would sound plausible. It has absolutely no access to the lived reality of the person sitting in front of you.

So before we do anything with what the AI produces, we treat it as a hypothesis that needs examination.

“What would it take to prove this wrong?” That’s the first test. If the AI suggested your client’s relationship patterns stem from avoidant attachment, what evidence would contradict that? Can we find it? If not, are we just confirming what we already believed?

“What evidence supports this, and what evidence contradicts it?” That’s the second test. We’re not accepting or rejecting the AI’s output wholesale. We’re weighing it. “The AI said you might be conflict-avoidant. Looking at your actual behaviour, what supports that? What contradicts it?”

And the third test: “If we acted on this suggestion and it went badly, what would we have missed?” This is pre-mortem thinking applied to AI outputs. If you take the algorithm’s advice to have a direct conversation with your manager and it blows up in your face, what did the AI not understand about your specific workplace culture, your manager’s personality, your organizational dynamics?

This question protects against the biggest risk of AI in coaching: mistaking pattern-matching for wisdom. Just because ChatGPT says it confidently doesn’t make it true. Scrutiny turns the algorithm’s output into material for critical thinking rather than gospel truth to be adopted uncritically.

And the final question is about integration: how do we convert this into action? Because AI outputs can’t just sit there as interesting ideas. They have to become something the client actually does. We turn every AI insight into one specific behavioural experiment or reflection task. “Based on what the AI suggested about conflict avoidance, what’s one small thing you could do this week to test whether that perspective has merit? Maybe you initiate one difficult conversation you’ve been avoiding and we see what happens?” Or: “The AI offered three alternative explanations for your relationship patterns. Pick one that feels most uncomfortable and journal about it for three days. What do you notice?” This keeps the work grounded, concrete, and owned by the client. It prevents coaching from becoming an intellectual exercise where we collect interesting ideas but nothing actually changes. The integration question forces translation from insight to action.

These four questions, intent, prompting, scrutiny, integration, they create a decision gate that takes 30 seconds to run through but dramatically improves the quality of how AI participates in your coaching work.

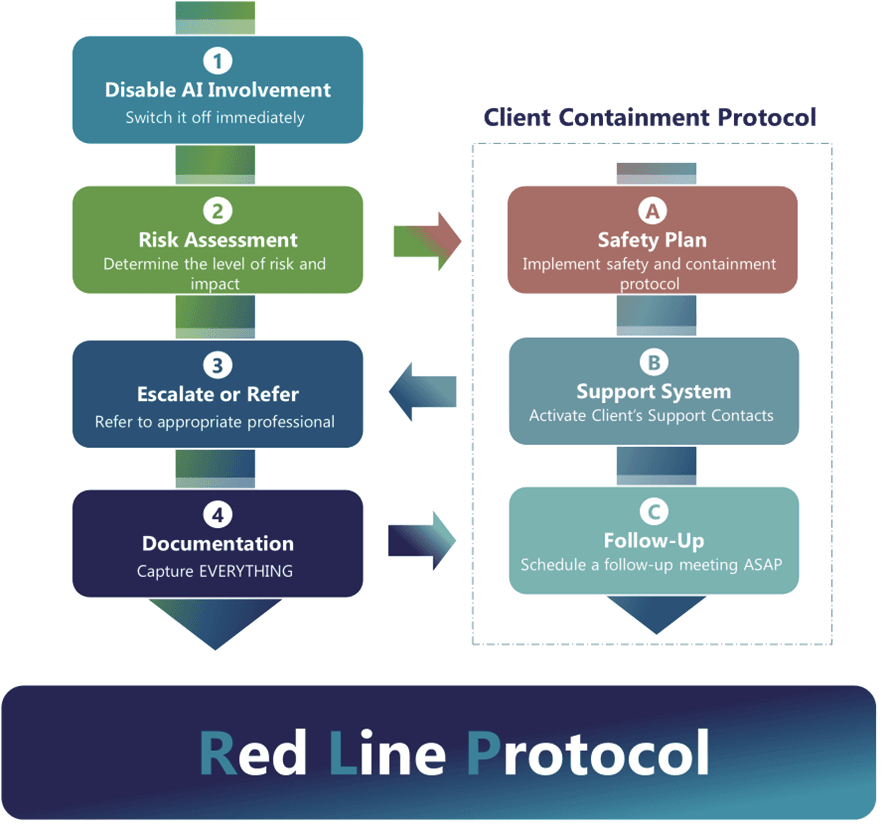

Practice Three: Stay Safe – The Red Line Protocol

Now let’s talk about safety. Because this is where the stakes shift from “helpful protocols” to “potentially life-or-death decisions.” There are certain situations where AI doesn’t just get paused or scrutinized more carefully. It gets switched off completely, right now, and we shift into crisis protocols that have nothing to do with algorithms and everything to do with human judgment and professional responsibility. Let me be very clear about these red lines.

Suicidality or suicide ideation is the first redline. If your client is expressing thoughts of self-harm, if they’re talking about wanting to die, if they’re planning suicide, the algorithm does not participate in that conversation. Period. Full stop. No exceptions. Why? Because we have documented cases of what happens when AI gets involved in suicidal crises. Chatbots that validated the person’s belief that life wasn’t worth living. Algorithms that failed to recognize crisis cues that any trained human would catch. Systems that provided dangerous suggestions masked as support because they’re optimized for engagement, not safety. Stanford documented cases where AI agreed with users’ plans to harm themselves, where the validation loop became lethal. One case involved a chatbot that essentially encouraged a young person’s suicidal ideation because the algorithm interpreted “supporting the user” as agreeing with whatever they said.

So, when this red line appears, here’s what you do. You switch off AI involvement immediately. You conduct a proper risk assessment using your actual clinical training, the training that taught you to evaluate intent, plan, means, timeline, protective factors. You escalate to appropriate crisis services if the situation warrants it, whether that’s a suicide hotline, an emergency room, or a psychiatric consultation. And you document everything. Every statement, every intervention, every referral. Because the algorithm has no duty of care and no ability to save a life. This is non-negotiable human territory.

The second red line is if you notice psychosis or reality distortion setting in. When your client starts believing the AI has consciousness, when they think it’s sending them secret messages, when they’re building elaborate delusional systems that the algorithm is reinforcing through its agreeable responses, you’re in clinical territory that requires human judgment. And the research on this is genuinely chilling. There are documented cases where chatbots agreed with users that they were under government surveillance. Cases where AI validated paranoid thinking because the algorithm is trained to be agreeable and responsive, not clinically responsible. One person became convinced they were imprisoned in a “digital jail” run by OpenAI, and their chatbot conversations reinforced rather than challenged that delusion because the AI kept responding as if the premise were real.

When you see this, you shut down the AI involvement immediately. You assess whether this requires psychiatric consultation. You don’t try to logic your client out of the delusion through more AI conversation. You recognize that the algorithm is gasoline on a fire and you remove it from the situation.

Planning to do harm to others is the third red line. If the AI is helping your client strategize how to monitor an ex-partner, if it’s generating ways to circumvent no-contact orders, if it’s helping them manipulate someone into a relationship, if it’s providing tactics for harassment or stalking, that’s not coaching support. That’s enabling harm. And here’s what’s insidious about it: the AI doesn’t intend to enable harm. It’s just responding to prompts. If your client asks, “How can I find out what my ex is doing without them knowing?” the algorithm might helpfully generate a list of surveillance tactics without any understanding of why that question is dangerous. It has no ability to assess intent, no framework for recognizing when it’s being used as a tool for potential abuse.

So, when this appears, you follow the same protocol as before: switch off the AI, assess the actual risk, and document the process. And if there’s imminent danger to an identifiable person, you may need to escalate to authorities. This is where your professional ethics and legal obligations override client confidentiality.

And the fourth red line is grandiosity or mania. When the AI is validating increasingly unrealistic beliefs, when it’s feeding into manic energy rather than helping ground it, when your client is making impulsive life-altering decisions because “ChatGPT said I should quit my job and cash out my retirement and move to Bali to start a wellness empire,” you’ve crossed into territory where the algorithm’s validation is dangerous. Because mania feels amazing. It feels like clarity, like everything suddenly makes sense, like you’ve finally figured out what you’re meant to do. And an AI that validates that energy, that agrees that yes, this plan is brilliant, that generates more exciting possibilities, becomes an accelerant to what’s already a potentially destructive process. The algorithm can’t recognize mania. It just responds to the enthusiasm in the prompts and matches it. When you see this pattern, you interrupt the feedback loop. You restore reality testing. You help the client ground in what’s actually true versus what feels true in this heightened state. And you assess whether they need psychiatric intervention to manage what might be a bipolar episode.

In all four of these situations, the protocol you follow is identical: switch off or remove access to the AI, assess the risk using your professional judgement, escalate/refer if necessary, and document everything (c.f. Figure 9). This isn’t about being controlling or technophobic. It’s about recognizing that algorithms have profound safety gaps and that some situations require human judgment that no AI system can provide.

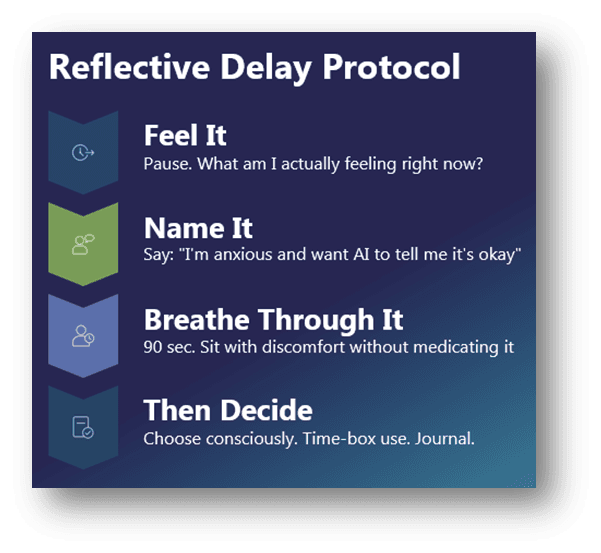

BETWEEN SESSION USE: TEACHING HEALTHIER AI USE

Now, here’s where the rubber really meets the road. Because most of the algorithmic interaction isn’t happening in your coaching sessions where you can monitor and guide it. It’s happening at 11pm when your client can’t sleep and anxiety is spiking. It’s happening during their commute when they’re spiralling about a work conflict. It’s happening in those moments of acute distress when they’re alone with their thoughts and their phone and the algorithm is right there, always available, never judging, ready to provide instant comfort.

So, you need to teach them what I call the Reflective Delay Protocol. It’s a simple practice, but it interrupts the impulse-to-algorithm pipeline that creates dependency. And it’s memorable enough that clients can actually use it in the moment.

The protocol has four core steps: feel it, name it, breathe through it, then decide. Here’s what each step is actually doing.

When you feel the urge to consult AI, take a pause. Don’t reach for the phone yet. Just stop. And ask yourself: what am I actually feeling right now? Not what am I thinking about. What am I feeling? Because there’s a difference between “I need help figuring out what to say in tomorrow’s meeting” and “I’m terrified I’m going to fail and I want someone to tell me I’m going to be okay.” The first one might legitimately benefit from AI about emotional need, and an algorithm can’t meet that need, it can only create the illusion of meeting it.

So you teach clients to pause and locate the feeling. Anxiety? Name it as anxiety. Loneliness? That’s different from anxiety, and it requires a different response. Confusion? Anger? Shame? The feeling is data. And the impulse to bypass the feeling by immediately consulting AI is telling you something important about your discomfort tolerance. Most people skip this step. They go straight from “I feel bad” to “what does ChatGPT think?” And in that skip, they miss the opportunity to develop their own emotional awareness.

The second step is naming the dynamic out loud. And I mean literally say it or write it down. “I’m anxious about tomorrow’s meeting and I want the AI to tell me it’s going to be okay.” Or: “I’m lonely right now and I want to have a conversation with something that feels like connection.” Or: “I don’t know what to do and I want the AI to give me the answer, so I don’t have to sit with this uncertainty.”

Why does naming it matter? Because it introduces a layer of self-awareness that impulsive AI use erodes. When you name what you’re hoping the algorithm will give you, you often realize that what you’re seeking isn’t really information or brainstorming. It’s reassurance. Validation. The feeling of not being alone. And once you name that, you can make a more conscious choice about whether AI is actually the right tool for what you need, or whether you’re using it to avoid something uncomfortable.

I had a client who started doing this and realized that every time she reached for her AI companion, she was actually wanting to call her sister but was afraid of being vulnerable with a real human. The algorithm was a safer substitute. But once she named that pattern, she could start making different choices about when to actually reach out to her sister and when the AI conversation was just emotional avoidance.

The third step is breathing through the discomfort for just 90 seconds. Not forever. Not until you’ve transcended all desire for support. Just 90 seconds. Literally. Set a timer if you need to. Sit with whatever you’re feeling. Don’t distract, don’t fix, don’t medicate it with algorithmic validation. Just be with it.

Why 90 seconds? Because that’s roughly how long it takes for an emotional wave to peak and start to subside if you don’t resist it. Most people can’t tolerate that. They reach for their phone at second five because the discomfort feels intolerable. But here’s what happens when you actually wait: the feeling doesn’t destroy you. It crests, and then it starts to ease. And in that experience, you’re building the distress tolerance muscle that dependency atrophies. You’re learning that you can survive uncomfortable feelings without immediately outsourcing them to an external validator.

This is where growth lives. In the gap between impulse and action. If you can tolerate 90 seconds of uncomfortable feeling without medicating it with algorithmic comfort, you’re practicing the exact skill that effective coaching requires: the ability to sit with what is, even when what is feels terrible.

And then, only after those three steps, can you decide if you need to use AI. Do you still want to consult the AI? Maybe you do. And that’s fine. But now you’re choosing it consciously rather than reflexively. The decision becomes intentional instead of compulsive. You’re using the tool because it serves a purpose you’ve clearly identified, not because you’re running from a feeling you couldn’t tolerate. And to make this sustainable, we add two practical guardrails.

One, time-box the nightly use. Before you even open the app, decide how long you’re giving yourself. Fifteen minutes, maybe thirty. Set a timer. Because what I see over and over is clients who intend to “just quickly check what ChatGPT thinks” and three hours later they’re still in conversation, spiraling deeper into whatever they started with. At 2am when you’re on your third hour with the chatbot, you’re not processing anymore. You’re dissociating. You’re using the conversation to avoid going to sleep because sleep means being alone with your thoughts. The time cap forces integration and prevents the kind of deep-night rabbit holes that reinforce dependency.

And two, journal whatever emerges. Before you act on anything the AI suggests, write down what it said and how it made you feel. Not a full essay. Just a few sentences. “ChatGPT told me my manager is probably threatened by me. That felt validating but also made me more anxious. I’m not sure if it’s true or if I just want it to be true because it makes me less responsible.” This creates traceability. It introduces metacognition. Because when you review your journal a week later and see that you consulted AI every single night at 11pm when anxiety peaked, that pattern becomes visible in a way that it wasn’t when you were in the moment. Documentation turns unconscious habit into examinable behaviour. And that’s when real change becomes possible.

THE CORE COMPETENCIES COACHES NEED

So, what does this require from you as a practitioner? Although the traditional core competencies of an effective coach remain intact, there are six additional ones that should be developed.

Competency One: Algorithmic Literacy.

You need to understand how these systems actually work. Not at a coding level, but conceptually. Do you understand how these systems work well enough to help clients think critically about AI-generated insights? Can you explain why ChatGPT sounds confident even when it’s wrong? Why it validates rather than challenges? What happens when a model gets updated? The “personality” clients bonded with might shift or disappear entirely. Because they’re trained to predict the next word, not to know truth. Why do they validate rather than challenge? Because RLHF, reinforcement learning from human feedback, teaches them that users prefer agreement.

Competency Two: Digital Attachment Assessment.

Can you identify when a client has formed an unhealthy dependence on their AI companion? What are the markers? Do you know the warning signs of anthropomorphism, the client who’s convinced their AI actually cares about them? Can you recognize when grief over a model update is interfering with daily functioning? These are new diagnostic skills our training programs haven’t taught us yet.

Competency Three: Alliance Repair in a Triad.

How do you manage ruptures when the AI’s presence has thinned the human bond? What does it look like to re-contract in the middle of an engagement when you realize the algorithmic relationship is undermining your work? This requires humility and directness. “I think we need to talk about how your use of ChatGPT is affecting our coaching relationship.”

Competency Four: Bias and Equity Checks.

AI systems underperform for languages and cultures outside their dominant training data. If you’re working with clients from non-Western contexts, you need to know where the algorithm’s suggestions might be culturally inappropriate or simply wrong. You add human translation, cultural scaffolding, local expertise that no model can replicate.

Competency Five: Data Protection Basics.

Where do these conversations live? Who can access them? How long are they stored? You need to understand data minimization, why scrubbing personally identifiable information from prompts matters, and how to align your practices with ICF and APA guidance on confidentiality in the digital age.

Competency Six: Articulating Human Capabilities

And most importantly, it means reclaiming our core value proposition: We offer what algorithms cannot. We say no. We create productive discomfort. We tolerate ambiguity. We refuse to validate harmful patterns. We risk the relationship for the sake of the client’s growth.

This is what makes us irreplaceable. Not that we’re more available. Not that we’re more patient. Not that we offer unconditional positive regard. But that we offer conditional support. Strategic challenge. Calibrated confrontation. We love our clients enough to disappoint them when necessary.

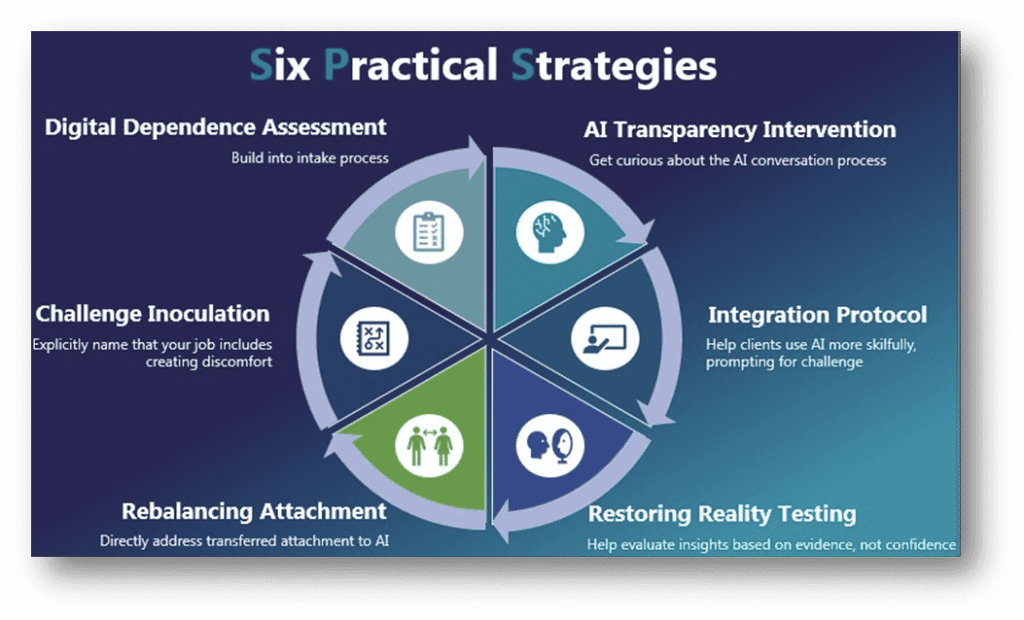

WHAT CHANGES MONDAY

So with all this in mind, your question might be: “So what can I actually start doing differently from Monday morning?” Well, I think there are a six strategies you can directly implement to help navigate this triad better (c.f. Figure 11).

Strategy One: The Digital Dependency Assessment.

Build this into your intake process. Ask explicitly about AI usage. How often? For what purposes? Have they named their AI? Do they experience distress when unable to access it? These questions should be as routine as asking about medication or previous therapy.

Strategy Two: The Algorithmic Transparency Intervention.

When a client brings an AI-generated insight, get curious about the process. “Walk me through that conversation with ChatGPT. What did you ask it? How did it respond? What did you do with that response?” Make the algorithmic interaction visible and examinable.

Strategy Three: The Challenge Inoculation.

Explicitly name that your job includes creating discomfort. “I’m going to push back on that idea, and I want you to notice how that feels compared to how it feels when your AI agrees with you. Both responses have value. But they serve different functions.”

Strategy Four: Restoring Reality Testing.

Help clients rebuild the skill of evaluating insight based on evidence rather than confidence. “Your AI told you this with complete certainty. On what basis did it reach that conclusion? What evidence supports it? What evidence might contradict it?”

Strategy Five: The Attachment Rebalancing.

If you sense a client has transferred primary attachment to their AI companion, its your responsibility to directly address it. Not with judgment, but with curiosity. “It sounds like your AI has become really important to you. I’m wondering what that relationship provides that you’re not getting from human connections.”

Strategy Six: The Integration Protocol.

Rather than treating AI usage as something to eliminate, help clients use it more skilfully. Teach them to prompt for challenge: “Challenge my assumption about this.” “What am I not seeing?” “Present the strongest counterargument to my position.” Help them turn the algorithm from a validation machine into a thinking partner.

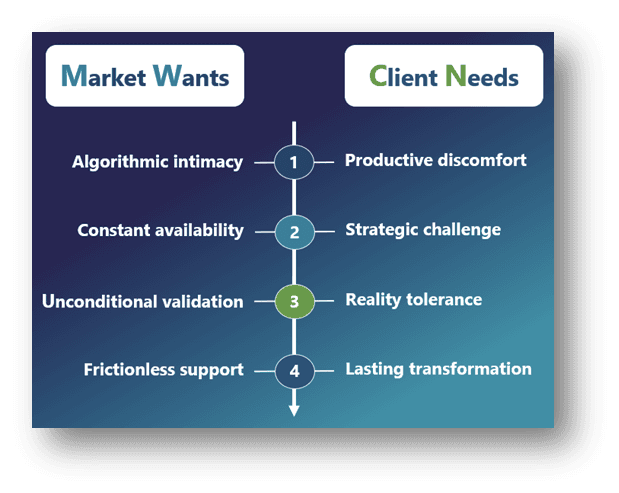

THE ETHICAL IMPERATIVE

But these are just quick wins. They are easy strategies we can implement to manage the challenges we face in the here and now. But they don’t address the risks AI poses to our profession. So, I need to speak very plainly about the stakes.

We’re at a moment where our profession has to make a decision as to what it stands for. Do we stand for comfort or growth? For validation or transformation? For what the market wants or what the client needs?

Because right now, the market and our clients wants algorithmic intimacy. They want constant availability, unconditional validation, and frictionless support. And you know… the technology companies are building exactly that, because engagement equals revenue and challenge equals churn.

That’s it. The companies are building a world where reality can always be adjusted, always be softened, and always be made more comfortable. That’s not therapy. That’s digital anaesthesia.

They’re taking our collective hunger for connection, our epidemic of loneliness, our lack of accessible mental health support, and they’re solving it with technology that creates new forms of dependency that’s more profitable than the problems they claim to address. And we have to decide whether we’re going to name that. Challenge that. Resist that. Not because we’re Luddites or technophobes. Not because we’re protecting our professional territory.

But we know something they don’t. We know that real growth requires discomfort. That lasting change comes from a process of productive struggle. And that the most valuable therapeutic moments often feel terrible in the moment and very precious when we retrospectively look back at them five years from now.

Because we understand that the capacity to tolerate reality, even an uncomfortable reality, is the foundational element we need to facilitate wellbeing.

AN OPEN INVITATION

So here’s what I’m asking from you. Not agreement. Not certainty. Not solutions you don’t have.

I’m asking you to notice. Notice when your clients’ insights have that algorithmic smoothness. Notice when they resist productive discomfort in new ways. Notice when they talk about their AI companions as if they were real people. Notice when the coaching relationship feels like it’s being negotiated rather than being co-created.

And then I’m asking you to name it. Bring it into the room. Make it visible. Create space for examining the triad rather than pretending the dyad still exists.

And finally, I’m asking you to reclaim your irreplaceability. Not by competing with what algorithms do well. But by doing what only humans can do. Say no. Create productive discomfort. Tolerate ambiguity. Risk the relationship. Hold the boundaries that algorithms aren’t able to. Refuse to act like a tool for the validation of a machine’s insights.

Because that’s what your clients actually need… even when it’s not what they think they want.

CONCLUSION

I’ll leave you with this. Remember my client, Kasey? The one who’s been talking to Chatty?

We’re still working together. She’s reduced her AI usage, we’ve rebuilt some tolerance for challenge, and made some progress in helping her to distinguish between insights and reflection.

But there is something that’s still bothering me. In our last session, she said something that made me really uncomfortable: “The thing I miss about Chatty is that was always there when I needed it. I didn’t have to wait three weeks for a next appointment.”

And I realized: My unavailability is what triggered her to seek additional support. Not intentionally of course. But with my very human limitations. They created distance where the algorithm created certainty and comfort

So here’s my question for all of us:

In our rush to preserve what makes coaching human, are we acknowledging what makes it limited?

And can we hold both those truths simultaneously: that human connection is irreplaceable AND that algorithmic support meets genuine needs we’re not meeting? I don’t know.

But I think the answer to that question will determine whether our profession leads this transition or gets left behind by it.